Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 4: Back to Moscow.

So far, our trade ambassadors from Holstein have sailed up the Baltic, traveled overland to Moscow, and been granted permission by Tsar Mikhail I to cross Russian territory into Persia. But Duke Frederick of Holstein must also sign the treaty and approve a first-year payment to the Tsar of 600,000 reichthalers. The ambassadors make the return trip in the dead of winter.

They spend three weeks in Reval, the modern city of Tallinn, and the journey is going well until February 2, when our intrepid author, Adam Olearius, is almost killed by friendly fire in the small city of Parnau.

If you’ve been with us since episode one, you’ve probably guessed how it happens: cannon fire. Towns invariably greet the visiting dignitaries by shooting off a cannon or three, and this time soldiers neglect to remove the tampion before firing.

The plug – which keeps dirt and moisture out of the barrel – narrowly misses his head and splinters violently against the wall of the city gate where he is standing. “Being stunned thereby,” Olearius writes, “it was half an hour ere I recovered myself.”

Seven hundred miles to the west, they reach Schonberg on March 31, where Olearius is shot by one of his companions. He describes it as “being casually shot in the arm with a pistol,” and takes three days to recover.

In Lubeck, he barely avoids being kicked to death by Johann von Mandelslo’s horse. You will remember from episode 2 that Mandelslo is a young friend of Olearius and former page to Duke Frederick.

They arrive in Holstein on April 6, 1635.

The Duke puts “all his thoughts toward the prosecution of the second Voyage, whereof the expense was incredible,” orders all necessary preparations to be made, and suitable gifts to be found for Tsar Mikhail.

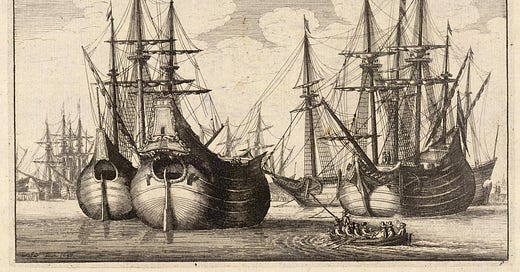

We are now in book 2 of the account, and at least 120 members of the new retinue leave from the harbor of Travemunde, near the city of Lubeck, on October 27.

Their brand-new ship, which Olearius does not name, probably for reasons that become immediately clear, has never been to sea. Before it can leave the harbor, a strong current pushes it into two other ships, where the rigging becomes entangled, and a full three hours of effort is required to separate them.

Olearius calls it an ill omen, and the situation goes from bad to worse. The next night, a “dreadful Tempest” driven by a West-South-West wind, pushes the ship hard. The brand-new ropes stretch, and the main mast threatens to slip out of place. The crew is “as raw as the ship was new,” and for the next few days both the captain and the first mate continually mistake their position on the sea.

The weather improves, and the Captain thinks they are near the island of Bornholm. In fact, they are closer to the shore of Denmark. They pass between Bornholm and the coast around 9 a.m. on the 29th. Twelve hours later, Ambassador Bruggeman asks the first mate “to be careful” in the dark, the sailor replies that there is no danger, and under full sail the ship goes aground on a rock just beneath the surface of the water.

“The shock made such a horrible noise, that it made all start up,” Olearius writes. “The amazement we were in surprised us so, that there was not any one but might easily be persuaded, that the end of both his Voyage and Life were near at hand.”

The night is black under a new moon. The ship is aground. They don’t know where they are. Hoping to attract aid, the crew lights a lantern and fires off some muskets. Nobody answers, and the ship begins to list. “Our affliction began to turn into despair, so that most cast themselves on their knees, begging of God, with horrid cries, that he would send them that relief which they could not expect from men,” Olearius writes.

“The Master himself wept most bitterly, and would meddle no further with the conduct of the Ship. The Physician and myself were sitting one close by the other, with a design to embrace one another, and to die together, as old and faithful friends, in case we should be wrecked. … Ambassador Crusius’s Son moved most compassion. He was but 12 years of age, and he had cast himself upon the ground, importuning Heaven with incessant cries and lamentations, and saying, ‘Son of David have mercy on me’; whereto the Minister added, Lord, if thou wilt not hear us, be pleased to hear this Child, and consider the innocence of his age.”

The sea pounds the ship upon the rock, but she does not sink. Around one in the morning the crew sees fire on an unknown shoreline. At daybreak, they see the island of Öland and the wreck of another ship.

Some local fishermen come aboard and effect a rescue, but one of the life boats capsizes and the team’s carpenter drowns. They are lucky he is the only casualty.

Many people from the island combine forces with the crew, the ship is wrestled free from the rock, and they sail her into Kalmar where she is found to still be sea-worthy.

On November 1, a Page and a Lackey are dispatched back to Holstein to fetch new letters of credential, the old having been lost to the sea. On November 3 they set sail again for Reval, passing by the island of Gotland and stopping to visit the city of Visby.

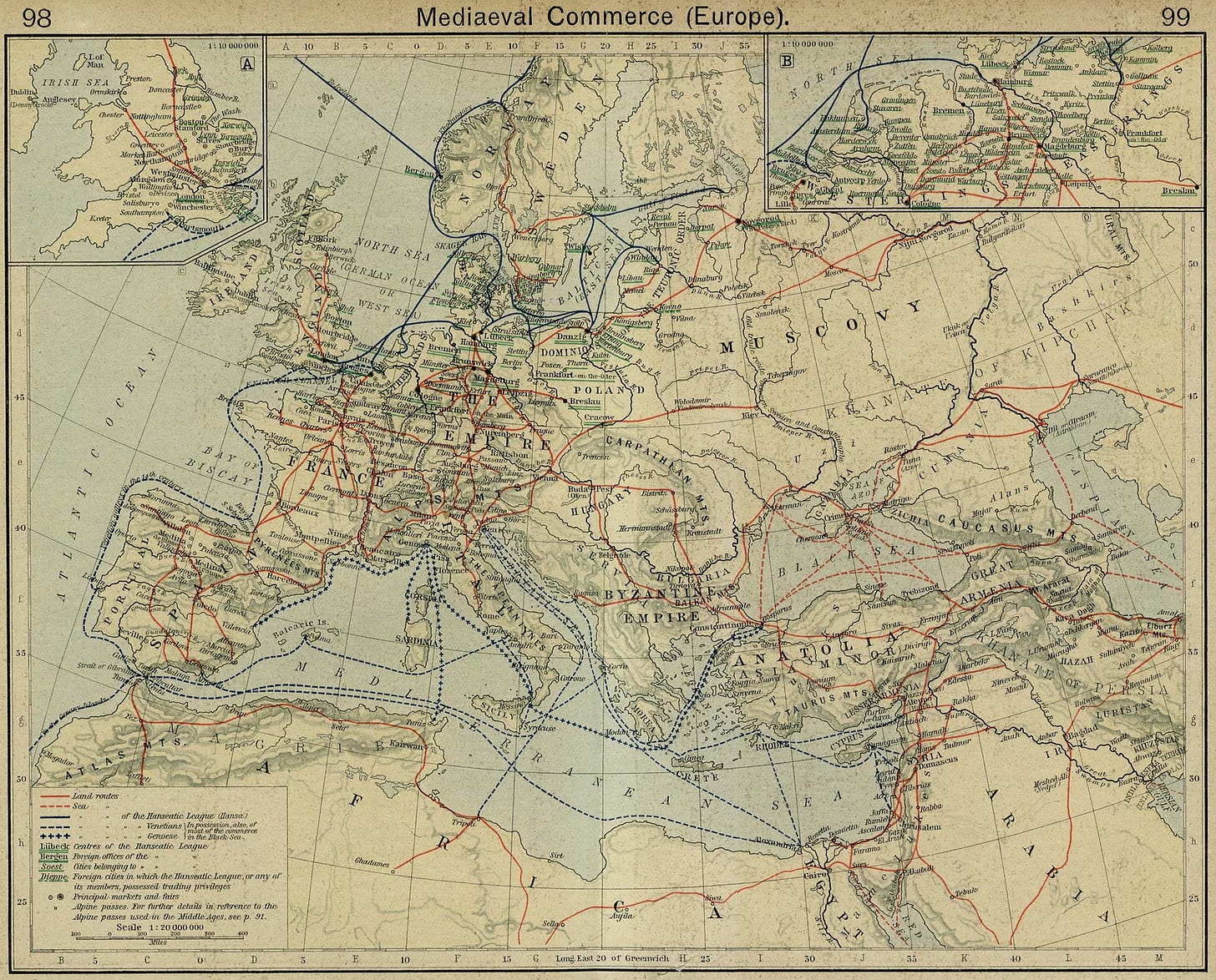

Sometime in the 13th century, towns and merchant communities in northern Germany formed the Hanseatic League, also called the Hansa, to protect their mutual trading interests. The League dominated commercial activity in northern Europe until the 15th century, and eventually dissolved in 1630, although the last official meeting didn’t happen until 1669.

These “merchants of the Roman empire” – as they sometimes called themselves – established outposts from Novgorod in the east to London in the west and member cities numbered more than 200 at the height of the League’s power.

The city of Visby, once called the Queen of the Baltic, was the wealthiest of all the early Hansa towns. The city had its own maritime code and coined its own money. As the story goes, five hundred warehouses were filled with goods, and treasures were hidden by nobles in their castles and by priests in the catacombs of a hundred churches. Traders built a city wall – rare for Scandinavia in the Middle Ages – to protect their wealth from other towns on the island. The conflict led to a civil war in 1288, and Visby was sacked but recovered.

A decade later, Lubeck was on the rise and Visby lost its Hanseatic privileges in 1299. She suffered another blow in 1349, this time from the Black Death.

In 1361, Valdemar IV, crowned King of Denmark as a young man, sought to reclaim lands that his father had mortgaged and plotted to overthrow the city.

Disguised as a goldsmith’s apprentice, Valdemar infiltrated the town and charmed the daughter of a wealthy Hansa merchant, who fell deeply in love with him. He proposed marriage, but said he needed a dowry from his family’s estate. Playing on her fear of the illicit affair, Valdemar said he would return in secret, present the dowry to her father, and they would board his ship for the mainland and be married. He needed but one favor: that upon his return, she should use her father’s key to open one of the city gates.

The maiden agreed. King Valdemar did return, and his beguiled bride-to-be did open the gate. The result was not marriage, but the rape of the Queen.

The Danes attacked, and a hastily assembled peasant army failed to halt the invaders. Valdemar’s soldiers plundered the town, put thousands of its citizens to the sword, and loaded their ships with treasure, astonished by the wealth they found. All was loaded until the holds of Valdemar’s ships could bear no more and they sailed for Denmark.

On the way west to Vordingborg, a storm sent by God drove the fleet south toward the Pomeranian coast, where all ships but the king’s were lost, and the treasure with them. Bodies and wreckage from the fleet washed up on the beaches of Usedom, today the most populous island in the Baltic.

As for the girl who betrayed her city, she was entombed alive by the townspeople, screaming for mercy as stonemasons built a wall around her. The Maiden’s Tower can still be seen in the remains of the castle.

The rivalry with Lubeck finally escalated into warfare, and a Lubeck fleet burned part of the city in 1525.

Such is the story of Visby, part fact and undoubtedly part fiction. Olearius mentions the Hanseatic League numerous times in his journals, so a bit of general history is in order.

The League was, in its own words, “a firm confederation of many cities, towns and communities, for the purpose of ensuring that business enterprises by land and sea should have a desired and favorable outcome, and that there should be effective protection against pirates and highwaymen.”

At the time, this association was more capable than any monarch of protecting the interests of merchants abroad, a situation which changed dramatically by the end of the Thirty Years War.

Aside from its many member cities, the League also had many trading posts – primary among them Novgorod, Bruges, London and Bergen – but none in Denmark, Poland, or Sweden, because those countries lacked three essential conditions: an important commercial center relatively distant from northern Germany, products in great demand, and privileges granted to merchants by local authorities.

The League also had no legal authority, per se, lacked its own official seal, and had no regular financial resources, fleet or army before the year 1550. This weak structure, and the fact that the League bore no responsibility for the acts of its members, was unacceptable to civic leaders accustomed to Roman law.

The League’s sheer volume of trade stood in stark contrast to its lack of central authority, but it was not powerless. It effectively used persuasion, arbitration and sanctions, and could exclude from its network any city or merchant that did not follow its rules. With foreign countries, it used negotiation, the creation or blockade of trade, and, eventually, war.

Voluntary associations of merchants also existed within the League that were simultaneously professional, religious, and recreational. The center of each association was a house with at least one big meeting room administered by the elders, elected by the general assembly of the members. In some cities, there might be an association of oceangoing merchants, while others specialized in a certain port or country. Merchants could also organize into trade companies similar to our modern general or limited partnerships. Every great merchant was a member of several trade companies at the same time.

But, as we know all too well today, even then the business of trade was too serious to be left in the hands of merchants, and by the 1600s the organization of the Hansa was no longer adequate. Large medieval city-states such as Lubeck, Stralsund, or Venice, had passed the height of their powers, and nation-states such as Germany, Sweden, and Italy began to take charge of security.

The merchant communities had, however, created a world economy that was rather like an empire without a head: an empire which avoided the heavy expenses of central government, and the wars imposed on its subjects by an all-powerful monarch. That world economy, and the merchant communities that created it, were unable to withstand the rise of hegemonic empires.

Meanwhile, on the sea east of Gotland, the ship bearing our ambassadors encounters another great Tempest “which kept us in action all that night and took away our main-mast, which was soon followed by the mizzen, and the forecastle,” Olearius writes.

The weather became so foul on November 8 “that it seemed rather an earthquake, that should turn the World upside down, than a storm.”

The wind pushes them eastward, past the haven of Reval, to the island of Hogland, and this time the ship does not survive.

“After the Ship had struck several times against certain pieces of Rocks, whereof there is abundance all along the Coast, it split and sunk. All the men were saved, a good part of the goods, and seven horses, whereof two died the next day.”

They shelter in fishing huts, without which Olearius says they would have died from exposure, and forage for food on the island. After surviving for a week, fishing boats ferry some of them to the mainland of Estonia on the night of November 18. The embassy had “roved two and twenty days upon the Baltic Sea, with all the danger that is to be expected by those who trust themselves to the mercy of that Element in so uncertain a season.”

The remaining men, horses, and baggage on Hogland are rescued three days later, and the entire complement are finally together in Reval on December 2, where they stay for three months.

Ambassadors Bruggeman and Crusius order Duke Frederick’s 15-point princely decree to be read aloud to the embassy. A short excerpt here will suffice: always obey the ambassadors; be guided in your actions by true fear of God; gluttony, drunkenness and other excesses are forbidden; everyone in the embassy must strive for harmony; everything must be done in such a way as to avoid disfavor and punishment from the Duke.

If you, dear listener, are saying to yourself something like “gee, I wonder how that worked out?” then you are an astute observer of human nature.

Of the edicts, Olearius writes “they were ill observed” and provides a couple examples.

First, Bruggeman arms his Lackeys with medieval battle axes which have pistols in their handles, and orders them to take no abuse from the citizens of Reval. Naturally, the men fall to fighting pretty much every day for the next three months.

And second, Bruggeman’s own servant, a Frenchman of “good humor and not quarrellous,” is killed while trying to stop a fight between said Lackeys and some Apprentices of the City. His murderer is never identified, and the Ambassadors compensate him only by attending his funeral.

The literary segue here is abrupt, and although I can’t pretend to think like a reader of 17th century travel magazines, I do think it is intentional.

Olearius give us the latitude and longitude of Reval, and notes that Waldemar, or Wolmar II, King of Denmark, laid its foundations about the year 1230. He notes that the city was once a Hansa town, but broke with the League in 1550, professes the Protestant religion, has a very fair school and a “democratical” city government that requires the mayor to “summon the principal of several Professions, and the most ancient Inhabitants, to consultations that concern affairs of Importance.”

On the 24th of February, 31 sledges are sent ahead to Moscow with “part of the train and baggage.” The rest of the group departs on March 2, and on March 5 they are in Narva once again, the country in between being described as full of bears and wolves that routinely attack the locals and their livestock. Naturally, Olearius has some stories about that.

In January 1634, a wolf – and not even the largest – killed three peasants who were bringing hay to the city: two had their throats torn out, one had his head torn off, and a fourth had his nose chewed off. Others finally killed the beast, and the Magistrate of Narva hung its pelt on the wall.

In the same year, a bear dug up 13 dead bodies from their churchyard graves and carried them away, while another bear broke int0 a brewhouse, got drunk on the ale, and fell asleep on the highway where pursuing peasants killed him.

Their Russian guide meets them at the border with 90 sleighs and 24 musketeers, and they proceed to Novgorod, formerly one of the great four Hansa trading posts, where we are treated to some friendly scientific competition and some terrible stories of human cruelty.

The city, Olearius tells us, is geographically situated at 58 degrees, 23 minutes elevation, and everyone else’s calculations are wrong. German historians Michael Lundorp and Johannes Sleidan put it at 62 degrees. Wrong. Paulus Jovius calculated 64 degrees. Wrong. Andreas Bureus, the former Swedish Ambassador to Muscovy, the father of Swedish cartography, and the founder of the Swedish National Land Survey – whom we met briefly in episode two – put Novgorod at 58 degrees, 13 minutes. Still wrong, but less wrong than the others.

“But at the exact observation I made of it on the 15 of March 1636,” Olearius tells us, “I found, that, at noon, the Sun was above the Horizon 33 degrees 45 minutes and that the declination of the Sun, by reason of the Leap-year, because of 55 degrees, was 2 degrees and 8 minutes, which being subtracted out of the elevation of the Sun, that of the Equinoctial line could be but 31 degrees 27 minutes, which taken out of 90 degrees there remains but 58 degrees, 23 minutes.”

Today, the Global Positioning System puts the city at 58 degrees 33 minutes.

This is the kind of detail I find interesting, and the bear stories were entertaining, if gruesome. But I’m going to skip most of what comes next, because Olearius writes almost a thousand words on the treatment of Novgorod by various tyrants of Muscovy. It will suffice to note that in 1567, similar to what happened at Magdeburg in episode 1, the Volkhov River was so full of corpses slain by the Tsar that its proper flow was impeded.

They leave the city on March 16 with 129 fresh horses, and a few days later they encounter a newly-married 12-year-old boy, which Olearius tells us is normal in Russia and Finland. Our translator Baron confirms it, saying that the Stoglav – a church council code written in 1551 – said anyone who reached age 12 could marry, and that it was a common stratagem between widows and boys whose parents had died, so they could keep their property.

The snow is beginning to melt, and rivers – where the ice is getting thin – are difficult to cross. On the River Sestra, below the crossing, they drive strong posts through the ice into the riverbed to prevent flowing ice from carrying their sleighs downstream.

They cross at least 10 rivers in 10 days, and arrive in Moscow on March 29.

In the next episode, we will find out if the Russians really are cruel and fit only for slavery, if the Tsar’s passport protects our embassy from robbers and violence, and exactly how many guns and soldiers they need to continue the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post