Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 26: Eclipse, Insurrection, and Murder.

The date is December 21, 1637, and we have made our way to Book 7 of the travel journal of Adam Olearius, the last of the series. Our trade ambassadors have survived the dangerous journey from Germany to the capital city of Persia, but, as we will see, Ambassador Otto Bruggeman’s actions have made the return trip even more dangerous.

Shah Safi informs the Germans that his pleasure requires them to travel through Kilan Province along the south shore of the Caspian Sea. Although it is one of the most fertile in the kingdom, Olearius tells us it is also home to Persia’s most cruel and barbarous inhabitants. And since Bruggeman has insolently and imprudently demeaned the shah on several occasions, the travelers are worried that this route is intended to be an instrument of revenge.

As Olearius writes, the route “raised an apprehension in some, that the king had given those orders purposely to ruin us.” In order to do that, all the shah has to do is “awaken the resentments of the governors of Derbent and Scamachie, whom Ambassador Bruggeman had indiscreetly affronted at our first passage that way.”

Five members of the mission are so worried that they join Lion Bernoldi in Isfahan’s sanctuary rather than travel with Bruggeman. You will remember from episode 22 that Bruggeman had threatened to murder Bernoldi after falsely accusing him of theft, and even sent soldiers to kidnap the man from the shah’s sanctuary.

The captain of their ship, Michel Cordes, his first mate, a guard, one of the pages, and the company’s surgeon, all decide to join Albrecht von Mandelslo’s journey into India rather than travel home with Bruggeman.

Olearius calls this “no small distraction.”

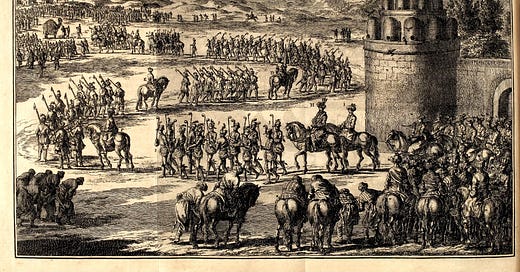

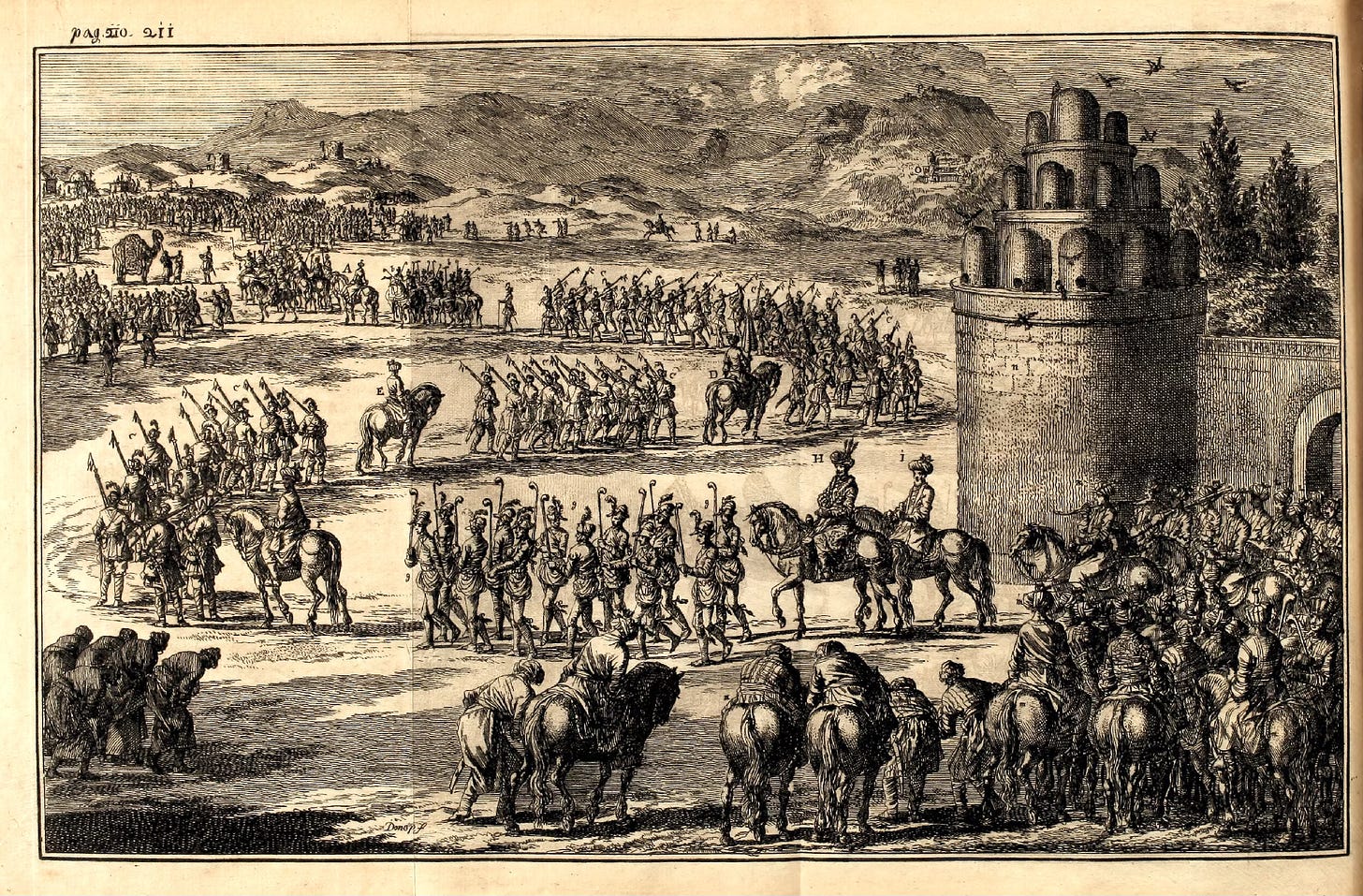

They depart on the evening of December 21. Most of the city’s English merchants, a few of the Augustinian monks, and the most important of the French merchants, bid them farewell a couple miles outside the city. Mr. Mandelslo travels with them on the first day, and then tearfully bids his friends adieu, his journey to India taking him east while Olearius continues north.

On Christmas day they pass the village of Kaskabath, where the shah is camped in tents of different colors, which makes for a very delightful show. They send a gentleman to pay the shah a compliment, which the shah accepts, and then continue on to their lodgings in the little city of Natanz.

They spend several days in Kaschan, and their Persian guide, who is fed up with being disparaged by Bruggeman, threatens to leave and report his ill treatment to the court in Isfahan. It takes Ambassador Crusius four days to reconcile the men.

On New Year’s Day they fire their cannons three times in celebration, listen to a sermon, make what Olearius calls “the ordinary prayers,” and then travel another five leagues to the village of Sensen.

In the city of Kom on January 3, they remind their Persian hosts that they were quartered in old ruined houses the last time they were in town, and thieves had stolen many of their things. In recompense, this time they are provided with very fair homes near the bazaar.

As they leave Kom early on the morning of January 5, Olearius reports a near-total solar eclipse. The sun was “not quite three degrees above the horizon when the moon deprived us almost of all sight of it,” he writes, “and so overshadowed it, that, to my judgement, in the greatest obscurity, the eclipse was three parts of four.”

According to a database compiled by America’s space agency, NASA, there were 248 solar eclipses in the 17th century, and four in the year 1638: January 15, June 12, July 11, and December 5. Obviously, NASA was not present in 1638 to witness the events. The dates have been calculated using a planetary theory called VSOP87, constructed in 1988 at the Bureau des Longitudes in Paris, France.

The theory estimates the relative positions of the sun, the moon, the earth – and the distances between them – with a calculated error of 1/40 second for each event. Using these calculations, NASA has built a 5,000-year catalog of past and future eclipses.

It doesn’t matter to me when Olearius witnessed the eclipse, but I do think getting the date right would have mattered to him. Did it happen on January 5 or 15? He’s not here to tell us, and he doesn’t make much of the event, either, possibly because other historical eclipses are more important.

For instance, early Babylonian clay tablets recorded a total solar eclipse in Ugarit, a port city in northern Syria, and modern calculations suggest it occurred on May 3, 1375 BC. “On the day of the new moon, in the month of Hiyar, the Sun was put to shame, and went down in the daytime, with Mars in attendance,” wrote the unknown Mesopotamian author.

Another eclipse is mentioned in Book 20 of Homer’s Odyssey, after Odysseus returns to his wife Penelope and finds her besieged by unwanted suitors. And so – on April 16, 1178 BC, if one believes NASA – Theoclymenus foreshadows the slaughter of the suitors that comes in Book 22: “among the wooers Pallas Athena roused unquenchable laughter, and turned their wits awry. And now they laughed with alien lips, and all bedabbled with blood was the flesh they ate, and their eyes were filled with tears and their spirits set on wailing. Then among them spoke godlike Theoclymenus: ‘Ah, wretched men, what evil is this that you suffer? Shrouded in night are your heads and your faces and your knees beneath you; kindled is the sound of wailing, bathed in tears are your cheeks, and sprinkled with blood are the walls and the fair rafters. And full of ghosts is the porch and full the court, of ghosts that hasten down to Erebus beneath the darkness, and the sun has perished out of heaven and an evil mist hovers over all.’”

And the crucifixion of Christ occurred on one of two possible dates, according to the NASA total eclipse data: November 24, 29 AD, or March 19, 33 AD. As Pontius Pilate allegedly reported, “Jesus was delivered to him by Herod, Archelaus, Philip, Annas, Caiphas, and all the people. At his crucifixion the Sun was darkened; the stars appeared and in all the world people lighted lamps from the sixth hour till evening; the Moon appeared like blood.”

As I was reading what the ancients made of these historical eclipses, I was reminded of something that happened to me forty years ago. When I was a senior at university, I told a professor of my dissatisfaction with the modern wall of separation between science and religion. He seemed surprised that I would think they should be joined – as they were for most of human history, as they were when Adam Olearius was watching that eclipse in Persia.

I don’t really know why I felt that way at the time, but I left that meeting more dissatisfied than when I arrived. Forty years later, we in the West are witnessing the collapse of that wall of separation. Scientists in every discipline are falsifying experiments in the service of ideology, other scientists are unable to reproduce the results of original experiments, and groundbreaking papers are being retracted for fraud. Unlimited amounts of money are enticing so-called scientists to say that science is just another word for consensus, and leaders of academic institutions are resigning in disgrace.

Like every other institution built by Western Civilization and torn down by social justice do-gooders, Science as we know it – the one with a capital S – may one day cease to exist.

Maybe that’s a good thing. I don’t know how I feel about it yet, but Science might die of shame on a day of a new moon, in the midst of a total eclipse, and return to the chaos from whence it came.

[Musical Interlude]

Sometime on January 6, Adam Olearius’ horse falls down dead in the harsh winter weather of the Persian plateau, and they slog through six inches of snow for the next 150 miles until they pass through the coastal mountains on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea.

Ambassador Bruggeman’s horse falls down under him, too, and not only is his right arm put out of joint, but he hits his head on the ground and his brains are so disordered that they fear he might never recover. They reach Saba that night, some 180 miles from Isfahan, and stay there all the next day in the hope that Bruggeman will recover his senses.

On January 8, they travel some 35 miles to Choskeru. “As soon as we were lodged in this caravanserai,” Olearius writes, “the Ambassador Crusius gave order for the seizing of certain seamen who had committed several insolences at Saba; but they put themselves in a posture of defense, and endeavored to make an insurrection in the retinue, in so much that we were obliged to disarm them by force, and to put them into irons, wherein they continued till our coming to Schamachie.”

This is the second insurrection experienced by the ambassadors. The first occurred just over a year earlier, and the ringleader is still in prison in the Russian frontier city of Terki, today the Russian city of Makhachkala in the Republic of Dagestan. Olearius told us in episode 8 that he would be retrieved from prison on the return trip, but we never hear of him again.

They meet an ambassador from Poland the next day at a caravanserai Olearius calls Hetzib. Today there is an abandoned caravanserai called Hajib in roughly the same location, but of course we can’t be certain they are one and the same.

“Having traveled about three leagues, near an old uncovered caravanserai named Hetzib, we met with a Lord whom the King of Poland sent Ambassador to the King of Persia,” writes Olearius. “His name was Theophilus de Schonberg, a person, though well advanced in years, of a very good countenance. He was a German by extraction, and yet in the discourse that passed between him and the Ambassadors, which lasted above an hour, he spoke altogether in Latin: but taking leave of us, he discovered himself to be a German. He told us, among other things, that the King his Master had given him a retinue of 200 persons, but that the great Duke of Muscovy would not permit him to pass with so many: which had occasioned him to stay six months at Smolensk, whence he had been forced to send back most of his people, and reduce them to the number he then had about him, which was, 25 persons. He also delivered us some letters from the Armenian Archbishop, whom we had met at Astrakhan, and told us, there were arrived in that city some provisions which had been sent us from Nizhny Novgorod.”

Sometime later, Olearius tells us that Schonberg is murdered, along with most of his retinue, by a “wicked and daring” group of barbarians in the region of Dagestan. Three survivors escape back to Derbent and eventually return home with a Russian embassy sent by Tsar Mikhael, the Great Duke of Muscovy. We will hear more about the barbarians of Dagestan in a future episode.

As they near Araseng, the harbinger returns with bad news. Sent to secure quarters for the night, he says the residents will cut the ambassadors’ throats if they try to enter the village. As Olearius writes, “They had not forgotten the affront which the judge of the village had received at our first passage that way, from the Ambassador Bruggeman, who having desired water to wash his hands, and the poor man having brought him troubled water such as the brook did afford, cast it in his face, and the pot at his head; so that we were forced to travel on.”

Olearius had refrained from telling us that story on the way to Isfahan, in episode 18, and now he tells us that three more villages deny them lodging for the same reason. They are forced to travel another 15 miles along a very bad road to the village of Kulluskur, and it is daybreak before they all find their beds.

Olearius find himself at the home of the local holy man, with whom he attempts to have dinner. The imam refuses his invitation several times, preferring instead to avoid the Christian man who is desecrating his house with wine and food forbidden by the law of Muhammad.

They reach the city of Caswin on January 11, and stay more than a week waiting for fresh horses and mules.

In the next episode, our intrepid travelers cross the mountains on the most dangerous and dreadful road in the world, after which they find themselves in a kind of terrestrial paradise, and we hear what kind of extraordinary punishment Shah Safi uses to execute one of his political rivals in this Caspian paradise, on the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post