Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 28: The Sign of the Seven Stars.

“Having travell’d two leagues, we were got to the Caspian Sea-side, whence we saw the Countrey, which is all cover’d with Trees and Forests towards the North and South, spreading itself like a Crescent a great way into the Sea, on the right hand, from about Mesanderan and Ferahath, and on the left, from about Astara. We travell’d about a league along the Caspian Sea-side, and lodg’d at night upon the Torrent Nasseru, in a house call’d Ruasseru-kura, which had but two Chambers in all, so that being streightned for room, most of our people were forc’d to lie abroad, at the sign of the Seven-Stars.”

The date is February 1, 1638, and our ambassadors are roughing it on the coastal road of the Caspian Sea. That is, Secretary Olearius and the other gentlemen are sleeping in a two-room roadhouse while everyone else sleeps under the stars.

The “sign of the seven stars” caught my attention as an artistic embellishment. If you live in England, you may recognize it as the name of the oldest public house in London – Seven Stars, founded sometime around 1600 and formerly known as the League of Seven Stars after the seven provinces of the Netherlands. Why the Netherlands? Because Dutch sailors had settled in the area and were among its first customers.

The Seven Stars was a popular name in the 1600s, with no less than 25 establishments around England using the name and issuing trade tokens emblazoned with the symbol. Merchants would hand out tokens to stimulate trade, or when small change was in short supply, and the token had to be good for some specified amount, product, or service.

The Seven Stars Inn of Manchester opened in the year 1350, and numerous establishments in the UK are still named The Seven Stars.

The London tavern is less than 10 minutes by foot from the Middle Temple, one of the four Inns of Court that train London’s lawyers. In the 17th century, law students used the temple hall to stage plays, and Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was performed there in 1602.

The name was so popular that Shakespeare referred to it in the History of Henry IV, Part I, which was written no later than 1597. Here is a short passage from Act I, Scene 2, in a London apartment owned by Prince Hal. Enter the Prince of Wales and the rogue Falstaff.

Falstaff. Now, Hal, what time of day is it, lad?

Henry V. Thou art so fat-witted, with drinking of old sack and unbuttoning thee after supper and sleeping upon benches after noon, that thou hast forgotten to demand that truly which thou wouldst truly know. What a devil hast thou to do with the time of the day? Unless hours were cups of sack and minutes capons and clocks the tongues of bawds and dials the signs of leaping-houses and the blessed sun himself a fair hot wench in flame-coloured taffeta, I see no reason why thou shouldst be so superfluous to demand the time of the day.

Falstaff. Indeed, you come near me now, Hal; for we that take purses go by the moon and the seven stars, and not by Phoebus, he, ‘that wandering knight so fair.’ And, I prithee, sweet wag, when thou art king, as, God save thy grace,—majesty I should say, for grace thou wilt have none,—

Henry V. What, none?

Falstaff. No, by my troth, not so much as will serve to prologue to an egg and butter.

Henry V. Well, how then? come, roundly, roundly.

Falstaff. Marry, then, sweet wag, when thou art king, let not us that are squires of the night’s body be called thieves of the day’s beauty: let us be Diana’s foresters, gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon; and let men say we be men of good government, being governed, as the sea is, by our noble and chaste mistress the moon, under whose countenance we steal.

Chief among Falstaff’s talents are thievery and drinking – “we that take purses go by the moon and the seven stars” – but the term “Seven Stars” does not derive from drinking establishments. Instead, it is the other way around: taverns took the name because travelers oriented themselves at night by the seven brightest stars of the constellation Ursa Major – also known as the Great Bear, the Big Dipper, or the Plough and Horses.

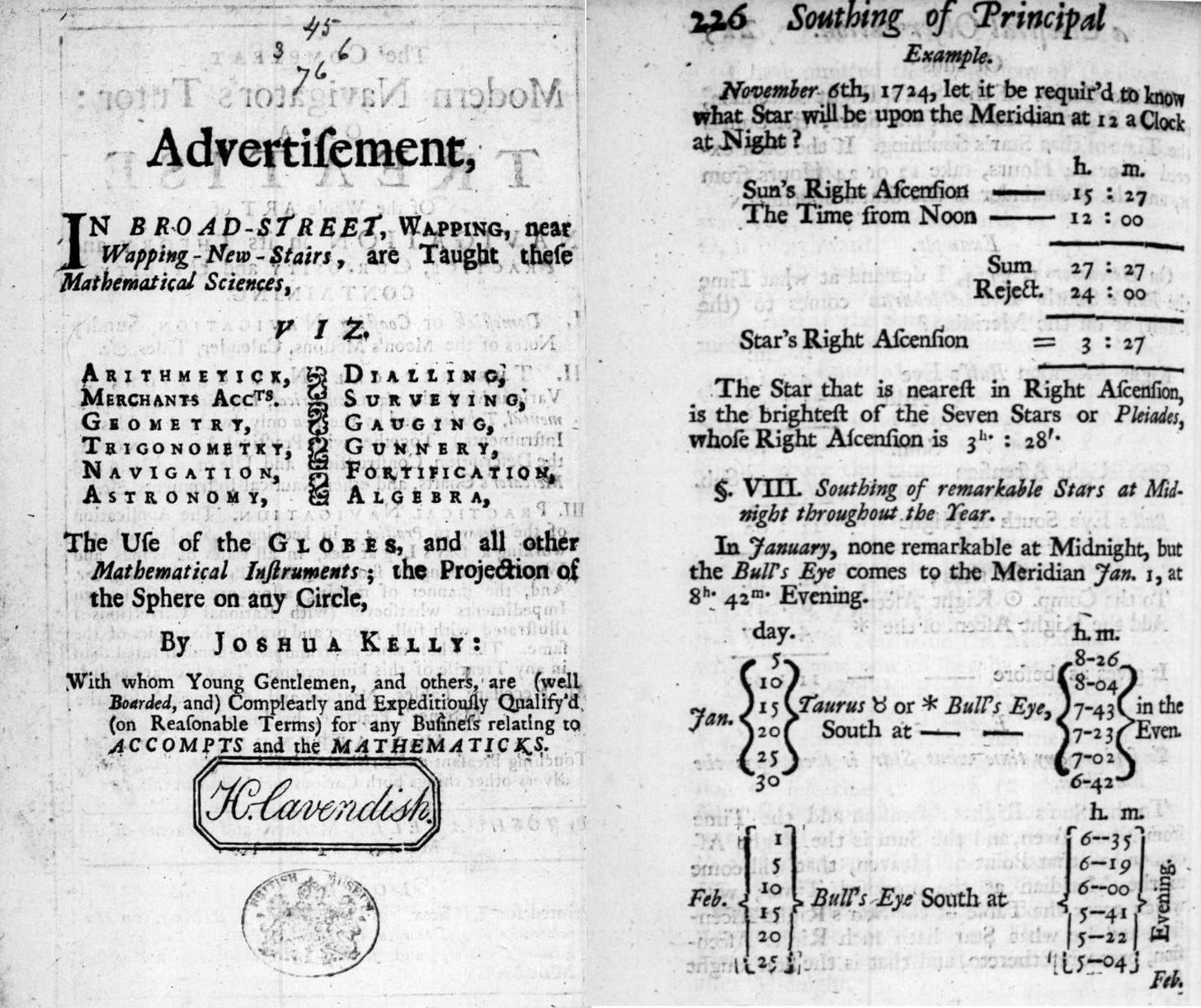

Or perhaps midnight travelers used the Pleiades – also known as the Seven Sisters and the Seven Stars – to determine their position. After all, as Joshua Kelly wrote in his 1724 book – titled The Compleat Modern Navigator’s Tutor: Or, a Treatise of the Whole Art of Navigation in its Theory and Practice, Curiosity and Utility – “let it be required to know what Star will be upon the Meridian at 12 aClock at Night” on November 6, 1724. And the answer, he said, is, “The Star that is nearest the Right Ascension is the brightest of the Seven Stars or Pleiades.”

Kelly advertised himself as a mariner and teacher of “the mathematicks” for “young gentlemen and others,” who could be “compleatly and expeditiously qualified for any business” relating – but not limited – to accounting, geometry, navigation, algebra, gunnery, and fortification.

His offices were in London near the Wapping New Stairs and the Execution Dock, which was used for more than 400 years to execute pirates, smugglers and mutineers who had been sentenced to death by Admiralty.

I could go on about the Seven Stars – the brand of Japanese cigarettes, the vacation resort in the Turks and Caicos islands, the Book of Revelation – but let us return to our German travelers via the Holy Land.

The three wise men who visited the new-born baby Jesus used a star to navigate their way to Bethlehem. No one knows for sure if it was the brightest of the Seven Stars, a comet, or a supernova. The men are known in the West as Balthasar, Gaspar, and Melchior.

Church tradition has it that Balthasar was a king of Arabia or Ethiopia, Gaspar was a king of India, and Melchior was a king of Persia. And it is said that Melchior’s family crest contained a shield with seven stars.

So we have arrived back in Persia. But our circuitous foray into the history of the seven stars is not quite complete. The question now is whether our English translator John Davies was faithful to the original text when he wrote that “most of our people were forc’d to ly abroad, at the sign of the Seven-Stars.”

The 1663 German edition by Olearius himself says “most people lie under the bare sky.” And the 1727 French edition by Dutch diplomat Abraham de Wicquefort says “most of our people were forced to stand and sleep in the air.”

So Davies – aware of the Biblical, cultural, and scientific significance of the Seven Stars to his English readers – used artistic license to illuminate the German accommodations on the night of February 1, 1638.

The next day, our star-crossed travelers cross 14 little rivers and cross the border into the district of Astara. Their new guide leads them off the highway, through a cornfield, and into the little village of Sengar-Hasara, which I can find only on the old maps, where they discover a dinner of five wild boars waiting for them. The local forests are well-stocked with the creatures, Olearius tells us, because the Persians do not eat them and thus are not much inclined to hunt them.

They leave on the morning of February 3 in snowy and rainy weather, continuing their U-shaped journey along a coastline that bears no resemblance to what maps show today. The first leg of the of the U, from the house called Ruasseru-kura to the village of Sengar-Hasara, takes them west-northwest around a bay pierced by 14 rivers. This seems to correspond roughly to a drive from the Shafa Roud Coast to Lisar Beach, but that’s just an educated guess because there is no bay there today.

The next leg of the U, from Sengar-Hasara to Hove-Limir, and across another 14 rivers, takes them in the opposite direction, east-northeast, and the road is so close to the sea that the horses are often in the water up to their girths.

“Some of our people fell, horse and man, into the water,” Olearius writes, “so that this proved one of the worst days journey we had,” not least because after seven large leagues – or some 30 miles – they are forced to stay the night in a wretched village where they are lucky to get a roof over their heads.

The coastline of the Caspian Sea – which is in truth not a sea at all, but the largest lake in the world – has changed radically over the centuries. Precise scientific readings of sea level were not possible before the 19th century, but archaeologists and geomorphologists have reconstructed what they might have looked like over the last 2500 years. Put simply, changes in climate and discharges from freshwater rivers have caused sea levels to rise and fall dramatically, with summer evaporation being the principal factor.

For example, the sea rose by at least three meters at the beginning of the 17th century – which could account for the observations of Olearius – and fell by three meters 100 years later. There was a rapid three-meter fall between 1930 and 1977, followed by another rapid 2.5 meter increase between 1977 and 1997 that was completely unexpected by the scientific community.

After receiving fresh horses, they leave the wretched village the next morning, February 4, crossing another 22 rivers on bridges so bad that three peasants and four horses fall off and drown. Six more horses die before the Khan of Astara meets them a couple miles from the village of Choskedehene, which means “dry mouth” because the sea is so shallow there that the fish cannot get into the river.

The Khan, who is making preparations to become Persia’s Ambassador to the East Indies, warns that Cossacks are actively raiding cities along the coast, and that the Germans should remain armed at all times.

They stay for two nights and reach Lenkeran on February 7, resting there for three days. Here, the Alborz mountains begin to curve away from the coast, making space for the vast heath of Mokan.

Somewhere in those mountains, Olearius writes, Shah Abbas had wiped out an entire village for “the abominable lives they led.”

“They had their meeting in the night time at some private houses, where, after they had made good cheer, they blew out the Candles, put off their Cloaths, and went promiscuously to the work of Generation, without any respect of age or kindred, the Father many time having to do with his own Daughter, the Son with the Mother, and the Brother with the Sister. Schach Abas coming to hear of it, ordered all the Inhabitants of the Village to be cut to pieces, without any regard or distinction of age or sex, and peopled it with others. I conceive, it is of the Inhabitants of these parts, that we are to understand what Herodotus affirms, of their going together, without any shame, and publickly, after the manner of Beasts.”

Our ambassadors are now in the modern country of Azerbaijan, having crossed the current border at the city of Astara, and they are about to cross the heath of Mokan. We were last here a year ago, in March of 1637 (see episode 14), and the round trip to and from Isfahan is about 1200 miles.

Jan Struys, a Dutch sailmaker who journeyed to Persia in 1670 along the same route as our German ambassadors, wrote that Mokan is populated by bandits, mutineers, and “all those sent to Exile whom the Shah thinks good to banish.” Thus, the roads through the heath are “very unsafe and incommodious to travel.”

The village of Elliesdu sits at the entrance to the great heath, and gives us a pretty good idea how remote agricultural lands are managed in the Persian empire. Shah Safi has assigned a military officer named Beter Sulthan to manage the village and its agricultural output. Sulthan lives some thirty miles away, although Olearius does not tell us exactly where. The houses of the village are wretched and occupied by sharecroppers who must work the fields. Olearius calls these farmers “soldiers” who are “obliged to cultivate” the land, and they are paid with tax revenue collected from citizens of the region.

As we heard in episode 16, villages like Elliesdu pay taxes to larger regional cities and religious institutions. We don’t know for sure, but Elliesdu might be one of the villages that supports the tomb of Sheik Sefi in Ardebil, which collects taxes in the provinces of Kilan, Astara, and Mokan.

When the Germans stop in Elliesdue for the night, Ambassador Bruggeman is mortally offended by one of the Persian soldiers and orders him to be beaten to death. The events unfold in the way we’ve seen before.

Bruggeman needs a place to sleep, so he tries to commandeer the first house he comes to. The soldier who owns the house says he is not required to quarter foreigners there, and hits Bruggeman’s horse on the head with a stick. Enraged, the ambassador dismounts and assaults the soldier, who fights back. Bruggeman calls for help, and several of his servants beat the soldier so badly that it is all he can do to crawl away into the neighbor’s house.

The incident could have ended there, but Bruggeman demands further satisfaction. He orders his servants to ransack the soldier’s house, and steal both his weapons and his horse. But he is still not done, for the next morning he orders the insolent man to be dragged into the street. The Persian guide objects, saying the soldier is so dangerously wounded that he cannot get out of bed. Of course Bruggeman doesn’t care, and the man is brought out of the house, undressed and covered only with a blanket.

Whereupon the ambassador “commanded an Armenian, who was an Interpreter for the Turkish Language, to beat him with a great Cudgel, after the same manner as he had been beaten the day before. This merciless Rogue gave him one blow over the arm, and another upon the side, wherewith he dispatch’d the poor man, who stirr’d a little afterwards; but when the Armenian would, by order from Bruggeman, have prosecuted the execution, he found the man quite dead. The Ambassador seeing him in that posture, said, “’tis very well, he hath what he deserv’d.”

Of course that is still not the end of it for Otto Bruggeman. He tells the guide that Shah Safi must further “revenge him for the affront he had received,” and if he does not, Bruggeman will return with his own soldiers and “do himself satisfaction.”

We are not told when this might occur, or what satisfaction Bruggeman requires, but we do know that murdering the offender was not enough.

The other Persian soldiers of the village are watching, and Olearius says he doesn’t know why they didn’t just murder the entire German delegation then and there.

“The other Soldiers made it appear by their demeanor,” he writes, “that they wanted neither will nor courage to express their resentment of the injury done them, and cut all our throats, and I know not whether it were the presence of the [guide] that prevented them from doing it; but certain it is, that it would have been no hard matter for them to do it, and that it was the effect of a miraculous providence that we escap’d that misfortune.”

They leave town and begin the journey over the heath. Their guide stays behind, but catches up that night and demands that Bruggeman return the dead man’s possessions to the widow and children, who had been left “in a very sad condition.”

The date is February 13, and Olearius ends this part of the story by recording the latitude and longitude of the little village of Elliesdu.

Two days later they are across the heath, which comprises an area of some 1200 square miles, and nearing the territory of the Khan of Schamachie. Thanks to Otto Bruggeman, they have reason to fear the Khan. As you will remember from episode 13, various disputes caused Bruggeman to call the Khan a liar and declare that either he would kill the Khan or the Khan would kill him.

As it happens, the Khan is camped at Tzawat, where a bridge of boats crosses the river and where the Germans must also cross.

“We had some reason to be distrustful of Areb Khan, by reason of what had happen’d between us at our first passage,” Olearius tells us. “But he made it appear that the Persians have this also common with all generous minds, that they can forget injuries. For he did us no unkindness; nay, on the contrary, as long as we were in his Government, he let slip no occasion of obliging us.”

The Khan, for his part, blames the interpreter George Rustan, who had delivered several bad reports about the Germans, and whom the Khan would behead if they ever crossed paths again.

They cross the river on February 17 and camp at the foot of the mountains on the 19th, discovering that the company’s painter, Thierry Nieman, is dead from the flux. They carry his body over the mountains, suffering through a freezing winter storm that makes the road almost impassable, and bury him in Schamachie on the 22nd.

Having stayed in the city a year earlier, Olearius makes only a few notes this time about dinners, entertainment, and the exchanging of gifts. He does, however, tell us a story – using the Khan of Schamachie as an example – about how the Shah expresses his level of satisfaction with local governors.

It starts with the arrival of a messenger, who waits a few miles outside the city so the governor must ride out to see him. When he arrives, the governor dismounts and takes off his sword, his coat, and his turban as a show of respect.

The envoy has a box covered in rich tapestry which contains one of two things.

The first option is a letter expressing the Shah’s love. As Olearius writes, “If the King’s favor be confirmed to him, the governor receives from the envoy a new coat, which he kisses at the collar, touches with his forehead, and then puts it on.”

The second, and less pleasant, option is an order to cut off the governor’s head, put it into the box, and bring it to the Shah.

If the governor has done something really bad, like losing territory to the Ottomans, he is strangled to death. Then his skin is removed and filled with hay, and the ghastly scarecrow is displayed on the road outside the city.

Olearius tells us the governor of Schamachie is summoned in this way, and, knowing which option awaited him, he asks the German ambassadors to accompany him to the meeting.

He is mounted on an excellent roan horse, carries no weapons, and is escorted by his two sons, 15 of his personal guard, and about 400 other men. A special troop of horsemen carry long poles, which bear the heads of Turkish soldiers and the flags the Khan had taken from them in battle.

On the way out of the city, the entire retinue stops to drink several times, and young lads dance for their entertainment.

The governor finds the envoy at the entrance to the King’s Garden, attended by three servants and holding the box in his hand. Following protocol, he walks to within 10 or 12 paces of the envoy and cheerfully takes off his coat and turban.

The envoy says nothing for a long while, which startles the governor and causes him obvious, if momentary, discomfort.

“Shah Safi sends thee a Garment, and a Letter of Favour,” the messenger says, “Thou art certainly belov’d of the King.”

“May the King’s wealth continue forever, and may every day of his be as a thousand,” replies the governor. “I am one of the King’s old Servants.”

Then, in a posture of submission, he accepts a new coat made of sea-green satin and a new turban, and his retinue prays for the prosperity of the King, the success of his soldiers, and the health of the Khan. And all the people answer, Allah, Allah, Allah.

The ceremony ends with trumpets, and the Khan returns to the city preceded by the riders bearing the Turkish heads. He invites our ambassadors to dinner, but he has imbibed too much and the party ends early.

A month later, March 22 is Maundy Thursday – the Thursday before Easter that commemorates the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper – and the Armenians of Schamachie perform the ceremony of the washing of feet. The priest washes the right foot of the men, the left foot of the women, and then makes the sign of the cross on their feet with consecrated butter.

When the ceremony is finished, the priest is put into a chair by twelve men, who raise him into the air with exclamations of joy, keeping him there until he promises to treat them with a dinner.

The Armenian new year begins on March 25, which also happens to be Easter, and so they make a great procession out of the city. The Khan makes an appearance and Olearius describes the entertainment.

“The Armenians stood with their banners, crosses and images before the Khan’s tent, which they did only to please the Persians. … The Armenian women gave us the divertisement of their dancing, in three companies, which successively relieved one another. And The Khan gave us another kind of sport by letting loose among the people, two wolves, tied to long ropes, to be drawn back when they pleased. He caused also the head of one of those wild beasts to be cut off at one blow with a scimitar. That night I was stung by a Scorpion.”

In the next episode, we discover an ancient defensive wall built between the Caspian and the Black Sea, we find out how much salt the King of Tzumtzume could eat in one day, and why Jesus raised him from the dead, on the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post