Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 27: Paradise and Punishment.

Before we get started, this episode is almost six months overdue. There are quite a few reasons for the delay, including some health problems and important family affairs, but there is only one reason you’re just hearing about it now: I am not in the habit of giving the Internet details of my personal life and schedule. I hope you understand.

And so, where were we? Our ambassadors are in the northern Persian city of Caswin, about 50 miles from the Caspian Sea, and near their lodgings is a tree full of nails and ribbons. A saint who once performed miracles is buried under the tree, and a holy man at the site collects alms and offerings from people who come for healing from toothaches, fevers, and other diseases.

The process of being healed involves nails, hope, and sometimes ribbons. First you touch the troubled part of your body with the nail. Then you place your mouth as high on the tree trunk as you possibly can. Then you pound the nail into the tree at that spot. And finally you hope that the symptom of your illness is eased by the ritual.

As our author Adam Olearius explains, people with strong imaginations are cured, and they express their appreciation by tying a ribbon to one of the tree branches.

The healing is not free, of course, and the alms collected by the holy man encourage impostors to set up shop at other trees where no saints are buried.

The Germans leave Caswin on January 20, 1638. Fifteen miles to the west, they spend the night in the small town of Achibaba, which, we are told, was named after an old man who lived there in the time of Sheikh Sefi, the mystic Sufi master whose name was taken by the Safavid dynasty.

Allah performed a miracle for the old man and his wife – who were then near 100 years old – by reviving what Olearius calls “the heat of younger years” and giving them a son.

The modern name of the town is Aghababa, but some sources refer to it as Aqbaba. Aside from census data and weather reports, there is very little information about the town, but one nugget makes up for all that is missing. To find it, we have to travel forward in time to the year 1921. For in 1921, the little town of Aqbaba served as the launchpad for a mostly-bloodless coup by Col. Reza Shah Pahlavi and the Persian Cossack Brigade that ended the reign of the Qajar dynasty, which had ruled the country since 1785.

As the 20th century dawned, Persia was overrun with Russian and British spies, and both major powers maintained military forces in country. In 1907, without even informing the Persian government, London and Moscow divided the country into three sectors: the British zone in the southeast, the Russian zone in the north, and a neutral Persian zone in the southwest.

The Persians were shocked, and hostilities broke out almost immediately. In 1908, forces hired by Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar and funded by the Russians attacked the National Assembly and dissolved the Parliament that was attempting to form a new constitutional government. The Parliament building was shelled, several of its members were executed, and the Russian commander proclaimed himself military governor general of Tehran.

An unexpected and popular uprising united ethnic, religious, and pro-Western factions, the insurgents overwhelmed the Russian-led troops, and the Shah’s 12-year-old son replaced him on the throne. Russia attacked Parliament again in 1910 and sent troops over the border in the north. In the south, the British did nothing.

Then came the oil companies, World War I, and the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Squeezed by greater countries jostling for international position, Persia found herself occupied from every direction.

After the Great War, more than 100,000 Persians died of starvation and cholera, and 10,000 villages were abandoned. Fearing a post-revolution Bolshevik invasion, the British Army occupied key regions of the country and launched a failed attempt to take the northern city of Baku, situated on an oil-rich peninsula that juts into the Caspian Sea.

British diplomats crafted an Anglo-Persian Treaty, and – in a nation-building effort that would be all too familiar to us today – foreign experts flush with cash descended on the country to create a national army, drill for oil, build railroads, supply arms, and reorganize the national finances.

The Bolsheviks, meanwhile, published secret wartime plans that made the British look like the imperialists they were, and in 1919 the Persians – tired of foreign schemes – rejected the Anglo-Persian Treaty.

On February 20, 1921, Col. Pahlavi – whose nickname was “Machine Gun” Reza because he carried the regiment’s Maxim machine gun – led 600 Cossacks from Aqbaba to Tehran and took control of the government. A newspaper editor named Seyyed Zia ed-Din Tabatabai was made Prime Minister. Pahlavi took over as War Minister.

Two years after the coup, Seyyed Zia appointed Pahlavi as Iran’s prime minister. In 1925, the national assembly deposed the last Shah of the Qajar dynasty, and amended the constitution to allow selection of Pahlavi as the Shah of Iran. The dynasty he founded lasted until the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

Achibaba, Olearius tells us, is at “the foot of the mountain” – the mountain being part of the Alborz range between Caswin and the Caspian Sea – and the road passes through fruitful country where the people of Caswin graze their cows on plentiful, excellent good grass.

The vice-mayor of Caswin accompanies our ambassadors for a time, entertaining them with the story of his life. Born in Georgia to Christian parents, he had been kidnapped by Shah Abbas, and brought to Caswin as a slave. His parents remained Christian, but outwardly accepted Islam to avoid death.

This situation, as we have seen in previous episodes, is a common occurrence, and although Olearius does not say, the vice-mayor might also be a eunuch. After all, Shah Safi’s chamberlain and chief justice are both white slave eunuchs from Georgia, and slave eunuchs govern eight of the fourteen biggest Persian provinces.

They start up the Alborz mountains on January 22, and cross the same winding river more than 30 times before reaching the next village. The peaks are colorful but not very high. By noon they can see nothing but steep cliffs.

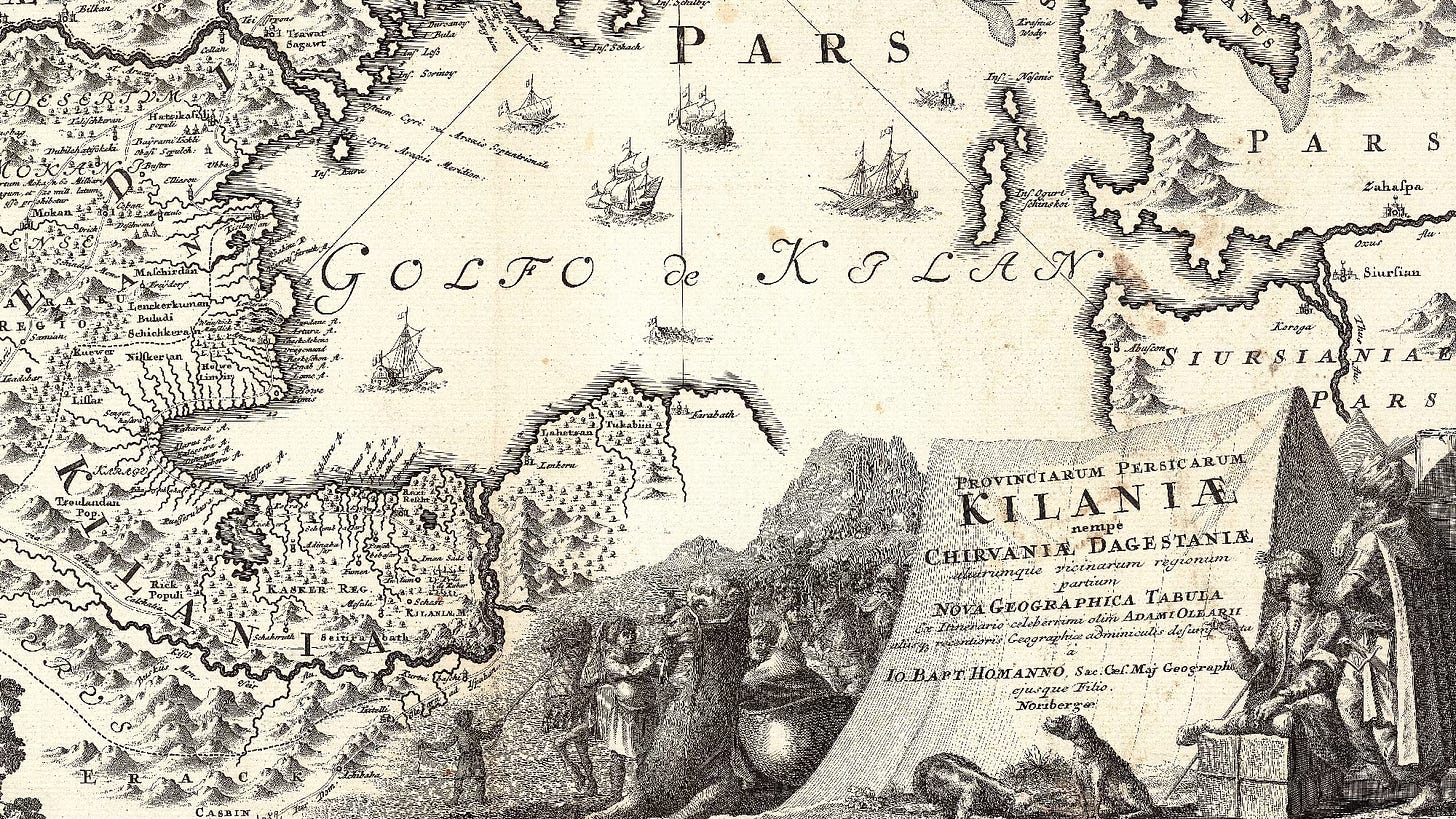

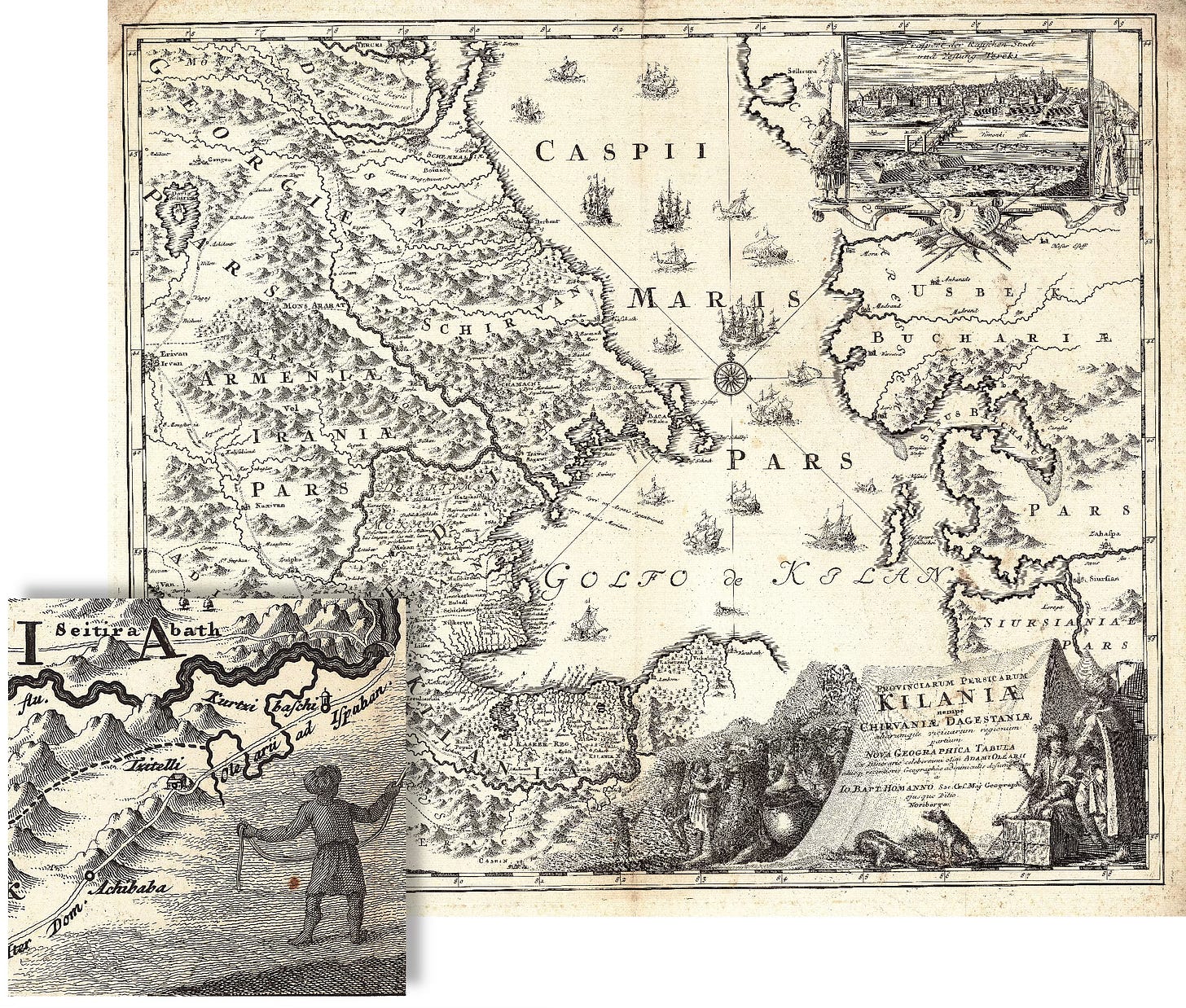

The mountain road is noted plainly on a 1738 map by Johann Baptist Homann, and it is the only map I’ve found that explicitly mentions any part of the German trade route. Along the river road outside Achibaba, Homann writes, “Olearii ad Ispahan” – Olearius to Isfahan.

Born in Bavaria in 1664 and educated at a Jesuit school, Homann worked as a civil law notary in the 1680s, moved to Nuremberg in 1691, and founded his own publishing house in 1702. It is not clear where he learned engraving – possibly in Amsterdam – but he became one of Germany’s leading cartographers, and in 1715 was appointed Imperial Geographer by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI and named a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin.

Homann died in Nuremberg in 1724, and the map mentioning Olearius was published by his son Johann Christoph in 1728. Details of Kilan province and the western shore of the Caspian Sea come from Olearius. The roads linking the region’s cities do not appear on Olearius’s original maps, but they do appear on Guillaume De l’Isle’s earlier map of the Caucasus mentioned in several previous episodes.

And although De l’Isle included the roads, he did not notate his map with the name of Olearius as Homann did.

On both of the old maps, the road from Caswin heads northeast to Achibaba. On modern maps, Aghababa lies to the northwest along the Qazvin-Rasht Highway. I’m not a mapmaker, and I can’t explain this discrepancy, but on all maps the road from Caswin leads over the mountains to the town of Rubar, on the Safidrud river. The Encyclopedia Iranica notes that the name “Rubar” is common in Iran and is sometimes causes confusion.

“In order to avoid such confusion, this district was often called Pildeh Rudbār (“Pyle Rubar” according to Olearius)” and refers to the “deep cut of the Safidrud valley, the only one to cross through the Alborz chain.”

On January 23, the road leads through a forest of olive trees to a narrow passage, anciently called the Fauces Hyrcaniae, that leads to Kilan province and thence to the Caspian.

The word fauces today refers to the narrow opening at the back of the mouth into the throat, from the Latin word meaning throat or gullet. It might also be related to the word faucet.

As noted in episode 8, the Caspian Sea was once known as the Hyrcanian Sea, from the Greek Hyrkania, said to be from an Indo-European word meaning “country of wolves.”

Olearius tells us that two rivers meet here, falling with dreadful noise through the rocks under the name of the River Isperuth. Passing under a stone bridge, it divides itself into several channels and eventually falls into the Caspian Sea.

The Encyclopedia Iranica says the bridge was originally built by Shah Ṭahmāsp, replaced by a beautiful brick bridge by Shah Ṣafi, which was repaired in 1698 and destroyed in 1837. The temporary, unsafe, wooden replacement was rebuilt in the 1860s, and was finally replaced by a steel bridge in the early 20th century.

The description of the bridge and the mountain pass is worth quoting in full, for both the detail and the language.

“This is a very fair Bridge built on six Arches,” writes our translator John Davies, “each whereof hath a spacious Room, a Kitchin, and several other conveniences, lying even with the water. The going down into it is by a stone pair of stairs; so that this Bridge is able to find entertainment for a whole Caravanne. At the end of the Bridge, the road divides itself. One way leads through a delightful and even Countrey, into the Province of Chalcal, and so to Ardebil, the other goes streight into the Province of Kilan, and this last is the most dangerous and most dreadfull way of any, I think, in the World. It is cut out of a Mountain which is pure Rock, and so steepy, that they found it a hard matter to make way enough for the passage of one Horse or Camel loaden, nay, in some places they have been forc’d to supply it with Mason’s work, where the Rock fell short. On the left hand, the Rock reach’d up into the Clouds, so as that the top of it could not be seen; and on the right, there was a dreadfull Abyss, wherein the River made its passage, with a noyse, which no less stunn’d the ear, than the Precipices dazzled the eye, and made the head turn. Not one among us, nor indeed of the Persians themselves, durst ride it up, but were forc’d to lead their Horses by the Bridle, and that at a distance loosely, lest the beast, falling, might drag his Master after him. The Horses came very gingerly, but the Camels stumbled not at all, and were sure to set their feet in the steps, which had been purposely cut for them in the Rock. At the top of the Mountain, we came to a house, where certain duties are paid. The Receiver thereof made us a Present of several fruits, and we wondred much, considering the time of the year, to see the Hedges all over the Valleys, flourishing, and full of blossoms.

“But this very Mountain, which was so steepy, teadious, and dreadfull on the one side, had so pleasant and delightfull a descent on the other, that it was no hard matter for us to forget the fright and trouble we had been in, in coming it up. It was all over clad with a resplendent verdure, and so planted with Citron-Trees, Orenge-Trees, Olive-Trees, nay, Cypress-Trees, and Box, that there is not any Garden in Europe could more delight the eye, nor more surprise and divert the smell. The ground was in a manner cover’d with Citrons and Orenges, insomuch that some of our people, who had never seen such abundance of them, made it their sport to fling them at one another’s heads. But what we were most astonish’d at, was, in one and the same day, to see Winter chang’d to Summer, and the cold, which we had been sufficiently sensible of in the morning, turn’d to a heat, which in a manner accompany’d us into Europe. We lodg’d that night, at the foot of a Mountain, upon the River Isperuth, at the Village of Pyle-rubar. ‘Tis true the houses were little and incommodious, and scatter’d up and down without any order; but there was not any but had its Garden, and Vineyard, its Citron-trees, Orenge-trees, and Pomegranate-trees, and that in such abundance, that the Village being cover’d therewith, we could hardly see any of the houses. It was encompass’d of all sides with a very high Mountain, save only, that on the South-west side of the Valley, there was a little Plain.”

Today, the region is covered by Lake Farah, a reservoir of some 1.4 million acre feet of water that was created in 1961 by the 350-foot tall hydroelectric Manjil Dam which generates 87 megawatts of electricity.

The dam was inaugurated in April 1962 by the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, and dedicated to Empress Farah. A 10-foot-tall bronze statue of her was placed on the bank of the new lake.

As the widowed Empress explained in 2019, the Islamic revolutionaries “tried to smash it into pieces after we’d left but they couldn’t. So in the end they gave up and pushed me into a lake. Anyway I like to think that one day I’ll resurface.”

She also described a scenario that could have been ripped from the headlines of 1636. A few weeks after the Shah’s family had been forced into exile by the Islamic Revolution, Farah said she received a message “from the madmen who had assassinated so many people back home. They said that if I could kill my own husband – poison him – then I would be allowed back into Iran. And if that doesn’t prove what kind of people they are then I don’t know what does.”

Three miles below the dam lies the town of Rubar.

The narrow pass between Manjil and Rubar is known as the Gates of Kilan, and the Germans have arrived at what Olearius calls “a kind of terrestrial paradise.”

“There is no Province in of all Persia so fertile and so abundant with Silk, Oil, Wine, Rice, Tobacco, Lemons, Orenges, Pomegranates, and other Fruits,” he writes. The grape vines are excellent, and as big as a man’s waist, but they are commonly planted beneath trees and the grape clusters grow high in the branches. Harvesters swing on ropes tied between trees to gather the fruit.

The mountains of the province are so covered with trees that it seems to be enclosed by one continuous forest, Olearius writes. The rivers and the sea are full of fish, the fields thick with cattle, and the forests teem with all sorts of venison and wild fowl.

The sea is cool and the land is warm, creating a steady evening breeze known as the wind of Manjil. Travelers observe that all the olive trees around Manjil are bent toward the south, and villagers say this points the faithful in the direction of Mecca.

Olearius tells us the province of Kilan is shaped like a crescent. On his map of the region, more than 60 rivers drain into the sea, creating a vast inaccessible marshland. But Shah Abbas, whose reign ended in 1629, fixed the transportation problem by building a 375-mile long causeway from Astarabad (the modern city of Gorgan) in the east to Astara in the west. Now, people may travel without any inconvenience by whatever means they prefer – carriage, horse, camel, or even wagon.

As noted in previous episodes, the kingdom inherited by Shah Abbas in 1587 had been invaded by the Ottomans in the west and by the Uzbeks in the east. Civil war had broken out between Persian factions. Abbas’s mother – the queen of the previous shah – had been murdered in 1579, and the grand vizier in 1583.

Abbas restored the breakaway Kilan province to the kingdom in 1591, but its leaders revolted again when Shah Safi ascended to the throne in 1629 and executed almost all the Safavid royal princes as well as the leading courtiers and generals.

A man named Karib-Shah, chosen as king of the province, immediately raised an army of 14,000 men, occupied all the cities, and seized the shah’s treasure. Safi, who was in Caswin at the time, commanded the governors of the surrounding provinces to besiege Karib-Shah’s army, but a strong defense repulsed the attack and caused heavy losses.

At this point, Olearius tells us, Karib-Shah might have improved his advantage and solidified his gains. Instead, he allowed his commanders to relax, and the soldiers “fell to merriment and making good cheer.”

The other governors noticed this mistake, reinforced their army with some 40,000 men, and routed Karib-Shah’s forces. He fled for his life to the city of Fumen, and asked a servant to save his life by exchanging clothes. The servant pretended to agree, but declared himself king after he had donned Karib’s garments and sword. “It is I who am now King, and thou art but a Traytor,” he said, and, calling to some of his comrades, seized Karib and brought him to Caswin to face the shah’s justice.

On the way into the city, Karib was jeered and mocked by five or six hundred courtesans. As we saw in episode 16, these prostitutes are often commanded by the shah to escort dignitaries into the city, singing and playing music, as they did with our German ambassadors.

Instead of music, Karib receives “a thousand indignities and affronts,” and the shah begins his execution by nailing horseshoes to his hands and feet. After three days, he is brought to the market square and tied to the top of a tall pole. If you remember the game of pole archery from episode 23, you will realize that Karib’s body is the target this time, instead of a melon or an apple. Olearius does not say if bets are placed, but he does say that the shah shoots first and “obliged all the Lords of the Court to follow his example, bidding those that loved him do as he had done.”

So many arrows pierce Karib’s body that “there was no shape of a man to be seen.” His corpse is left on the pole for three days, and then taken for burial.

The Germans leave Pyle Rubar on January 24, – passing a ruined castle and bridge which the locals say had been destroyed by Alexander the Great – and arrive at the city of Rescht the next day.

The city is on the floodplain between two rivers, where farmers grow corn and rice. The fields are interwoven with deep irrigation trenches, which Olearius notes are similar to those in Flanders. Gates and sluices channel water into the fields, but the bridges over the canals are “so ill kept in repair,” Olearius says, “that many of our people fell into the water.”

Situated about 10 miles from the coast, the climate gives Rescht the nickname of City of Rain, and Olearius writes that it is “the Metropolis of all Kilan.”

The city is “of a considerable bigness, but open of all sides like a Village, and the houses of it are so hid within the trees, that a man at his entrance into it may think, he is rather going into a Forest than a City, since there is no seeing of it, till a man be within it.”

Other travelers have also observed that the city looks more like a village. John Bell, who traveled there in 1717, noted that its “houses were scattered,” that it was located “in a plain surrounded by tall forests,” and that it looked more like “a big village.”

The marketplace is spacious and full of shops where all sorts of goods are cheap and readily available. The ambassadors stay in the city for five days and attend a festival similar to the one they had seen in Scamachie the year before.

They leave in the rain on January 30, traveling through a vast floodplain intersected by numerous rivers, and over bridges that strike fear into their stout German hearts. As Olearius puts it, all the rivers “have bridges, raised very high by reason of the frequent inundations, and so untoward to pass over, that they put a man into a fright.”

In spite of the care taken by the travelers, they could not prevent the doctor’s horse from falling into the river, “whence we had much ado to get him out, by reason of the Fens on both sides it.”

They arrive that night in the town of Fumen, where, as Olearius noted earlier, the rebel king Karib-Shah had been captured. By coincidence, it is also the birthplace of Shah Safi, the current ruler of Persia. His mother, a concubine of crown prince Safi Mirza, was “brought to bed” here by his father when the court of Shah Abbas journeyed into Kilan. The house where he was born belonged to a rich merchant, and afterward was converted into a sanctuary. We heard some of the family history in episode 22, in which Abbas had Safi Mirza executed, had his other sons blinded, and so was forced to elevate his grandson to the throne.

On the last day of January, the khan greets the Germans outside the little city of Kurab with 100 horsemen, accompanies them to their lodgings, and sends them a gift of four wild boars.

The khan’s name is Emir, the son of a Georgian Christian born in a village near Erivan, a border city contested by the Persians and Turks for centuries and today located in the country of Armenia.

Emir had been circumcised in his youth, Olearius tells us, had been a cup-bearer for Abbas, and was given his governorship by Shah Safi for military service rendered at the siege of Erivan in 1636.

He is an eloquent person, and takes much delight in discussing the affairs and wars of Germany and the manner of German life.

“He told us he could not forbear loving the Christians,” Olearius writes, “but we were told one very extraordinary thing of him, and horrid to relate, to wit, that having some time been in a tedious disease, which having caused a universal contraction in all his members, the physicians had ordered him one of the most extravagant remedies that ever were heard of, which was, ut rem haberet cum cane foemina.”

Translator John Davies – perhaps intentionally – does not translate that last phrase from Latin into English. I’m not certain what “universal contraction in all his members” means – perhaps it was some problem with the muscles in his limbs. In any event, it appears that Khan Emir’s doctors believed the cure was to have sex with a female dog.

In the next episode, the Germans experience one of the worst days of the journey, they discover that Cossacks are actively plundering coastal cities and murdering unwary travelers, and we find out what gruesome deed Shah Abbas visited upon an entire village after hearing of its promiscuous work of generation, on the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post