Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 24: Suburbs, Inflation, and the Great Pox.

As we continue our exploration of Persia’s capital city of Isfahan, that city is featuring prominently in current military events. Iran’s April 14 missile and drone assault on Israel was the first-ever direct attack on Israeli soil from within Iran’s borders. Israel responded by bombing an airbase just outside the city of Isfahan and an air defense facility in Natanz. Isfahan is no longer the capital of Iran, but the region, about a thousand miles east of Israel, is home to a major missile production complex and several nuclear facilities.

As we heard in episode 18, our ambassadors traveled through the little city of Natanz on July 28, 1637. The local caravanserai had several springs of fresh water, and was well stocked with fruit. Jan Struys, a Dutch sailmaker who journeyed to Persia in 1670 and spent three nights in Natanz, said it was “a very pleasant little city” with diligent inhabitants and very fertile country that produces “great plenty of good wine.”

A nearby mountain tower had been built by Shah Abbas in memory of the time one of his falcons killed an eagle on that very spot. We don’t know exactly where that tower was, but Natanz is a high desert city situated at the base of the 10,000-foot Karkas Mountains. Today, the Natanz Nuclear Enrichment Facility is located about 18 miles north along the Persian Gulf Highway, and is said to be producing weapons-grade uranium in a factory estimated to be up to 300 feet underground.

Adam Olearius writes that the Taurus Mountains divide Persia much like the Apennine range does Italy, “thrusting forth its branches here and there into several provinces, where they are called by other particular names.” His 1655 map of Persia puts the Taurus range in the center of the country – with, as he says, branches to the north, south, and east of Isfahan – and the 1730 map of Guillaume de L’Isle also makes use of the name. But there is no such range on modern maps of Iran, and I am left to conclude that Olearius is referring to what is now called the continuous central mountains that includes Mount Gargash, the home of the Iranian National Observatory. We know the Taurus Mountains as a range in southern Turkey that runs parallel to the coast of the Mediterranean Sea.

The provinces south of the central mountains are very hot, Olearius tells us, but those to the north are milder and more temperate. The old kings of Persia took advantage of this geography, spending the summer west of the Caspian in Tabriz and the winter in Susistan to the east. In spring and autumn they lived in Persepolis, which is south of Isfahan but still 150 miles from the Persian Gulf, or in Babylon, which today is the Iraqi city of Baghdad. The shah in 1637 does much the same, although he may choose different cities.

Isfahan is the most commodious of any city, Olearius writes, and is just as good in winter or summer because the mountains are nearby and there is always some wind stirring, which cools the air in all the homes of the city.

“We had but too much experience of this change, and the inconveniences ensuing thereupon, and found, that the heats of the day, and the cold of the nights, are there equally insupportable,” he writes. “For, being forced to travel in the night, and that during the hottest season of the year, we felt there a cold, which deprived us of the use of our limbs, and made us many times unable to get off our horses, especially when there was an east or north wind: whereas, on the contrary, the south wind sent us sometimes such hot blasts as was ready to choke us.”

Surrounding Isfahan there are nearly 1500 villages, many of them engaged in manufacturing textiles. Every province in the country produces cotton, and the fields around Isfahan are intentionally flooded when the river rises with melting snow. If not for this, Olearius writes, the region would not be habitable because of the “excessive heats which reign there.”

Some say that when the river subsides, it leaves behind some kind of slime that “corrupts the air,” but Olearius says those people are mistaken. “For it is certain,” he writes, “some Provinces only excepted, which lie upon the Caspian Sea, there is not any place in all Persia, where the air is more healthy than at Isfahan.”

It is true that temperatures are high, especially in June and July, but the inhabitants are not much inconvenienced by it. Their vaulted apartments, and their halls and galleries with windows on all sides, are constructed to allow wind and air to circulate, moderating the indoor temperatures.

In winter, although it does freeze, the ice is not even as thick as a man’s finger, and it thaws as soon as the sun appears over the horizon. But the Persians use the cold months to store ice that can cool their drinks all summer long. To do this, they find a “commodius place that is cool and towards the North,” pave it with stone or marble, and pour water upon it. When one layer of ice forms, they pour on more water, and by this means, in one night, they make ice a foot thick. They cover it during the day, and continue the exercise for two or three nights, ending up with enough ice enough to serve them all summer.

Except for Kilan Province, the soil in Persia is generally bad – sandy and barren in the plains, full of stones, and growing nothing but thistles and reeds, which they use in their kitchen stoves because wood is so scarce. But in the valleys between mountains, the ground is very good. They use plows to cultivate the fields, and when the soil is good the plows are so large they can hardly be pulled by two dozen oxen driven by six men. The furrows are a foot deep, and two foot broad. The crops include rice, wheat, and barley, but no rye and no oats. They also grow millet, lentils, peas and beans.

The domestic animals are sheep, goats, buffalos, oxen, cows, camels, horses, mules, and asses. The ordinary food for horses is barley mixed with chaff, or rice mixed with straw. The Persians do not water their horses for an hour and a half after they have eaten, which is contrary to the custom of the Turks who water theirs immediately after feeding.

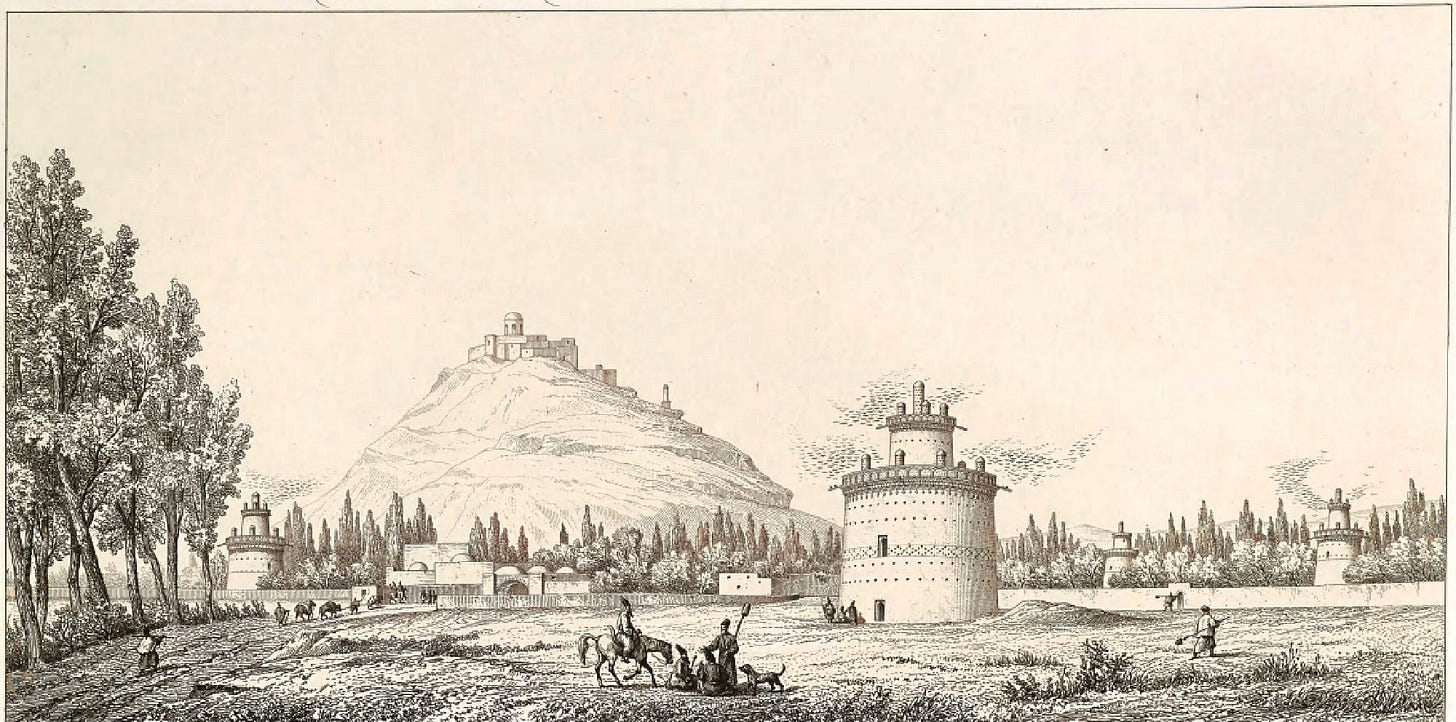

The city also has many large suburbs, and the fairest of all is New Julfa, which we have seen in several previous episodes and is occupied primarily by the Armenian Christians. On the other side of the river lies the suburb of Tabrisabath. Here live the people who were forcibly relocated by Shah Abbas from the province of Tauristan. For that reason it is sometimes called Abasabath. Christians from Georgia live in the suburb of Hasenabath. Like the Armenians, most of them are wealthy merchants. “They delight much in making voyages, especially to the Indies and into Europe,” Olearius tells us, and in Venice and Holland they are wrongly called Armenians.

No Christians live within the walls of the city, but Olearius says this is because they like it that way, preferring to “settle themselves in a place, where they might live quietly and enjoy the freedom of their conscience.” The Persians would allow them to live anywhere, not only because the shah benefits from trade and taxes, but also because the Christians tend the vineyards.

Islamic law forbids Muslims from drinking wine, and consequently the cultivation of vineyards. But the Persians are so fond of wine that they cannot go without it, and they imagine they commit no great sin – even if they drink to excess – as long as the vineyards are operated by Christians.

There is another noble suburb towards the west of the city named Kebrabath, deriving its name from a certain people called Kebber, that is to say, Infidels, from a Turkish which signifies a renegade. “I know not whether I may affirm they are originally Persians,” Olearius writes, “since they have nothing common with them but the language. They are distinguished from the other Persians by their beards, which they wear very big, and also by their clothing, which is absolutely different from that of the others. They wear, over their waistcoats, a coat which falls down to half the leg and is open only at the neck and shoulders, where they tie it together with ribbons. Their women cover not their faces, as those of the other Persians do, and they are seen in the streets and elsewhere and yet have they a great reputation of being very chaste.”

He tells us that he tries, and fails, to find out what religion the Kebbers follow, and assumes they are “a sort of pagan who have neither circumcision, nor baptism, nor priests, nor churches, nor any books of devotion or morality among them.”

In the northern quarter of the city lie two monasteries of Italian and Spanish monks, about a thousand paces distant from one another.

The Italian monastery is inhabited by 10 Carmelite monks who have, Olearius boldly affirms, no nobler convent in any part of Europe. Their prior’s name is Father Tinas, and he is a very ancient, very good man, having what is called a “free disposition.” They live among the Muslim infidels “in a much more orderly way than they do elsewhere,” Olearius says, and he feels himself obliged to “acknowledge their civilities, especially to those among us, who, having the advantage of the Latin tongue, could converse with them.” One gets the distinct impression that our Protestant author is none too fond of the Catholic Carmelites.

Formally known as The Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel, a religious order of the Catholic Church founded before 1214 AD, the Carmelites arrived in Isfahan in 1604 with Papal instructions to cultivate political ties to the Safavid court. According to modern sources, serious controversies arose within the order because the Pope’s instructions were contrary to their existence as a contemplative community detached from the world. And so they carried out the Pope’s orders only in the early years of the mission, and then began to engage Muslim elites in the hopes of converting them to Catholicism rather than some political alliance.

Carmelite Father Juan Thadeo de San Eliseo, who worked as a court translator in the 1610s and 1620s, debated with Muslim imams, translated Biblical texts and theological treatises into Persian, studied the beliefs and knowledge of his Muslim counterparts, and otherwise tried to be a Christian example instead of refuting the “ignorance” of the Muslims. He returned to Rome in 1629.

Later European observers in Isfahan say the Carmelites were humble in comparison to the Augustinians, who lived in a “splendid palace” and, by 1685, were interested in little more than “acquiring assets, buying carpets and doing similar business deals.”

In 1637, the Spanish convent, which we visited in episode 20, belongs to six Augustine monks who have built what Olearius calls a vast structure, including a church with two steeples, a stately cloister, several cells, and a large garden. The prior acted as the church’s permanent agent in the Safavid court, and he did Olearius a great favor by giving him refuge against the persecutions of Ambassador Bruggeman and ensuring that our secretary’s letters back to Germany were delivered “with much safety and speed.”

The French Capuchin order had sent three priests, who – when our ambassadors are in Isfahan – were beginning to build a convent within a quarter of a league of the monastery of the Augustines. They “seemed to be very good people, and had attained some learning,” Olearius writes. Before the Germans leave town, their chapel was finished, the dormitory was under construction, and a kitchen garden and a vineyard were being planned.

The Jesuits arrived in the 1660s, and the Dominicans in the 1680s, obviously well after Olearius returned to Holstein. Equally obvious is that a complete discussion of the Christian missionary presence in Persia is beyond the reach of this podcast, and that I have only briefly touched on a very complex topic.

His experience of the Persian weather proves to Olearius that not all the provinces of Persia are equally healthy, and there are some where diseases are much more common than in others. Shirvan and Kilan are very much subject to fevers, but the air in Tabriz is so good that no one gets a fever there. Dropsy, what we call edema, is common in Kilan province, but gout is not known at all, and it is ordinary to see persons reach 100 years of age.

In Kasan, the air is unwholesome and the pox is common even though that city is geographically “excellently well seated.” They also have tarantulas and the most dangerous scorpions in all of Persia.

In France, Olearius tells us, the pox is called the Neapolitan Disease. Today we know it as the sexually transmitted disease called syphilis. Syphilis had a variety of names, and people usually named it after the enemy or country they thought responsible for it.

The French called it the “Neapolitan disease,” the “disease of Naples” or the “Spanish disease,” and later the “great pox.” The English and Italians called it the “French disease” or the “Gallic disease.” The Germans called it the “French evil,” the Russians called it the “Polish disease,” the Polish and the Persians called it the “Turkish disease,” the Turkish called it the “Christian disease” or the “Persian fire,” the Tahitians called it the “British disease,” in India it was called the “Portuguese disease,” and in Japan it was called the “Chinese pox.”

The first epidemic of syphilis broke out in 1495 when Charles VIII of France invaded Naples with 50,000 soldiers and 800 camp followers, including cooks, medical attendants and prostitutes.

By the end of 1500 it had infected all of Europe, and after European sailors brought it to Calcutta, it spread to Africa, the near East, China, Japan and Oceania by the year 1520. In that year, the famous Dutch scholar Erasmus, said, “If I were asked which is the most destructive of all diseases I should unhesitatingly reply, it is that which for some years has been raging with impunity. What contagion does thus invade the whole body, so much resist medical art, becomes inoculated so readily, and so cruelly tortures the patient?”

The answer? The pox.

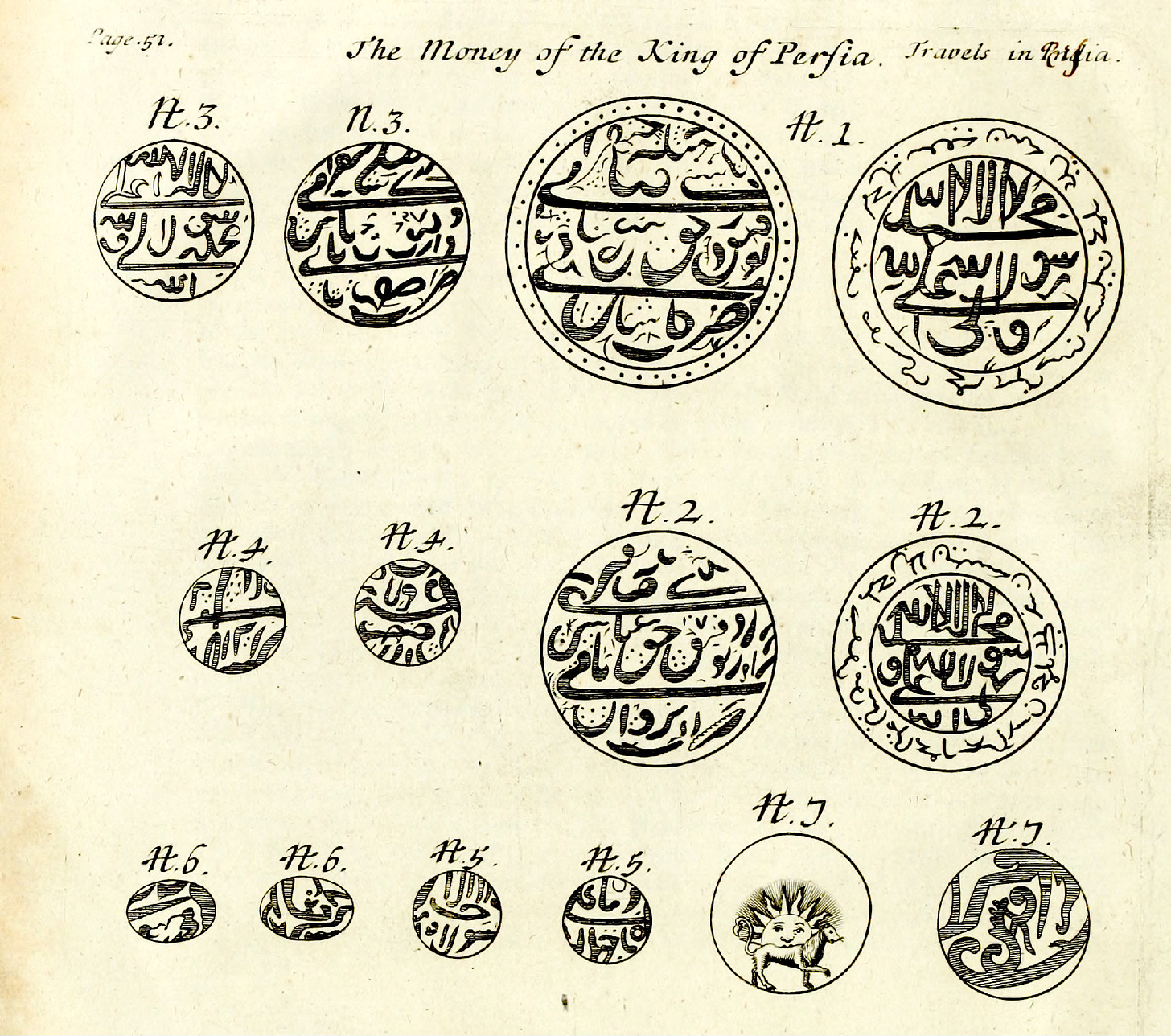

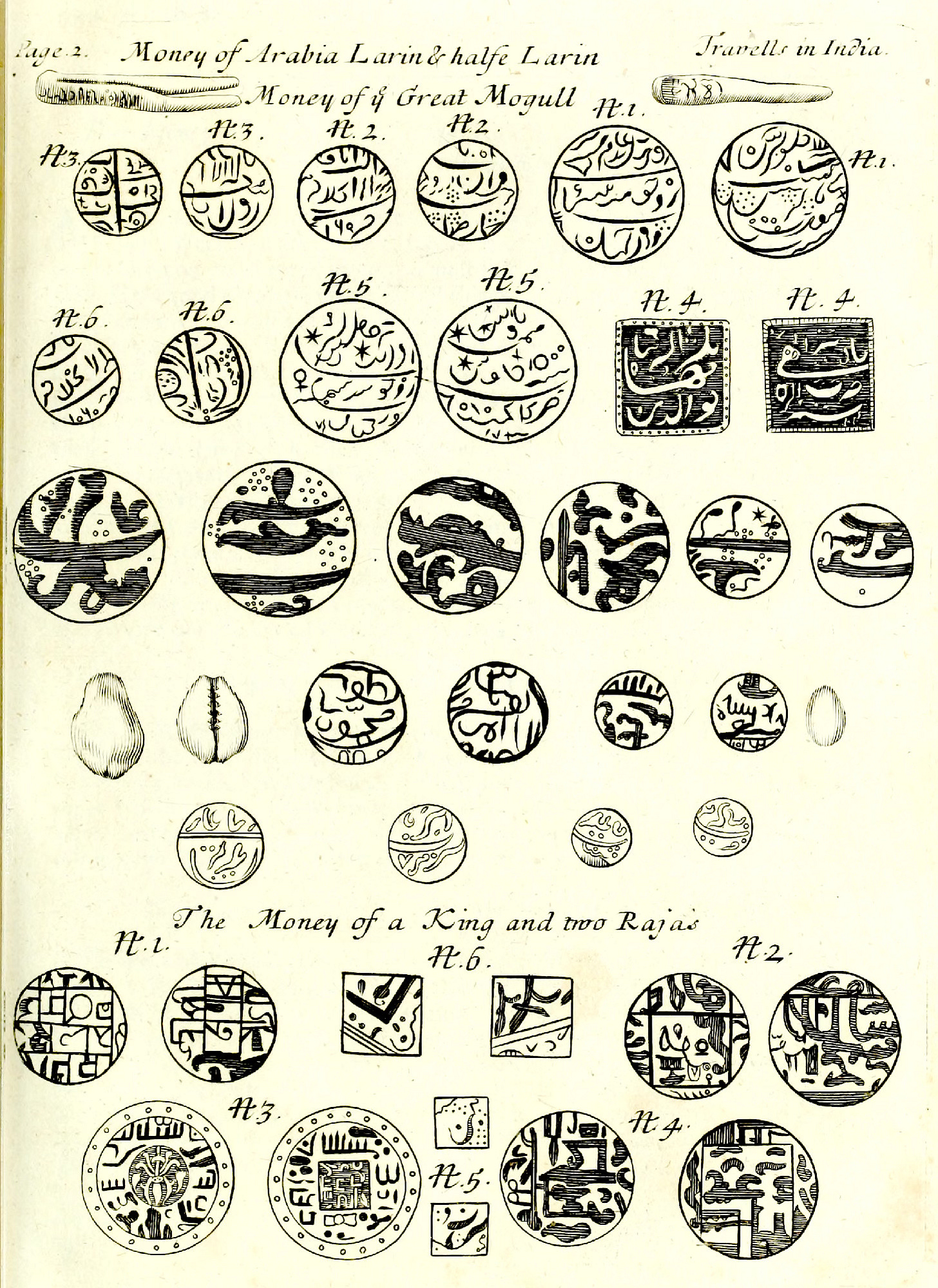

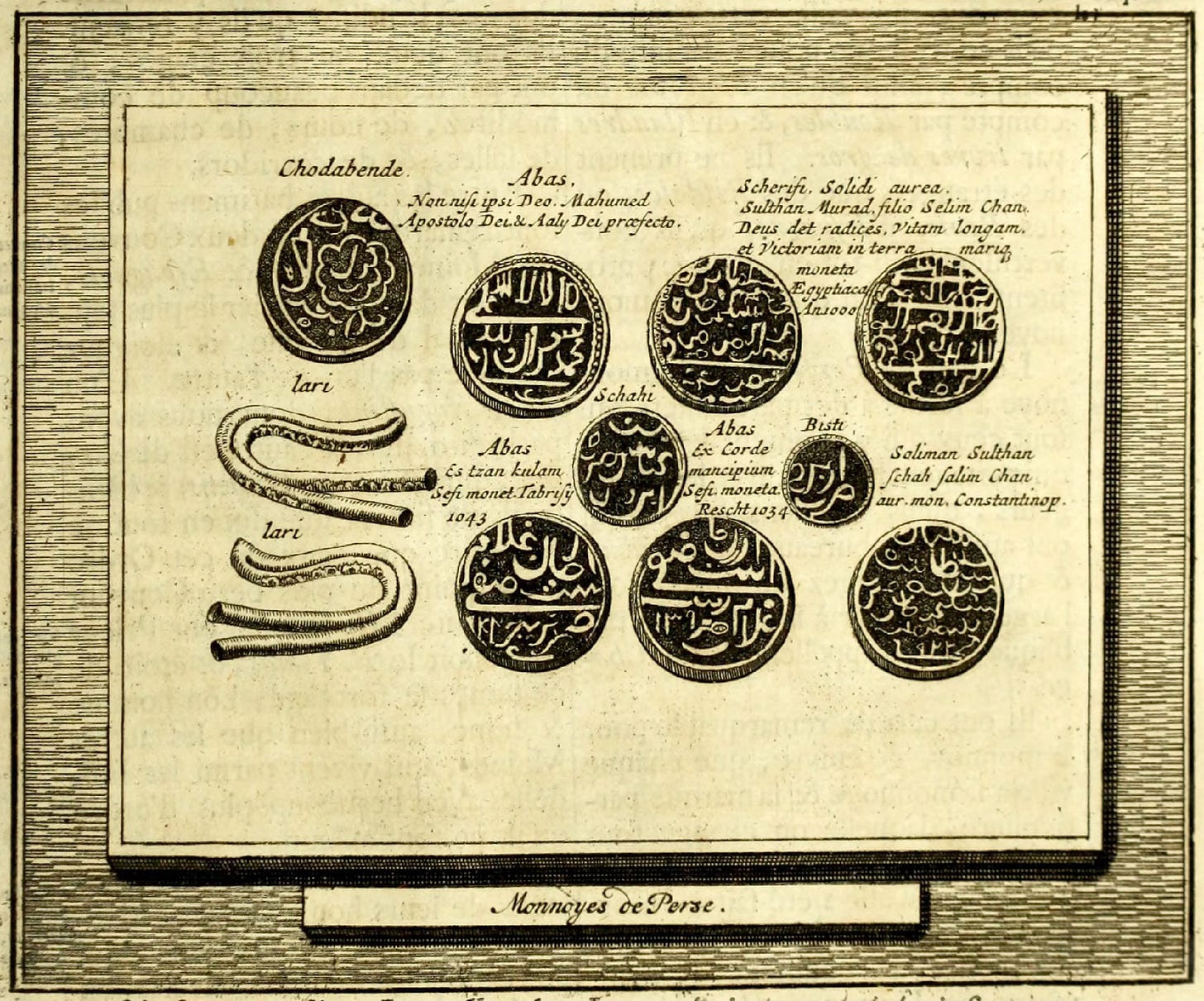

The ordinary money of Persia is of silver and copper. Gold is rare, and available only in foreign coins. Olearius describes the different minting marks, and tells us that every Persian city has its own money that is changed every year, and that such money can be spent only in the place it was minted. Modern historians say local money could be spent elsewhere, but was worth only half as much.

The ordinary marks include a stag, a deer, a goat, a satyr, a fish, a serpent, or other such things. In 1637, coins minted at Isfahan are marked with a lion, at Schamachie with a devil, at Kasan with a cock, and in Kilan with a fish. The shah’s face is on the other side.

On the first day of the year, which begins with the vernal equinox, “all the brass money is cry’d down and the mark of it is changed,” Olearius writes, using the word “brass” in referring to copper coins.

Thus, the copper coins minted by each governor retain their full value for only one year, after which they are returned to the mint to be melted down, reminted and reissued. Old coins do circulate, but only at half their value, and so are avoided by merchants and international traders.

The practice is intended to take “clipped” coins – by which a sliver of metal is cut off, reducing its weight – out of circulation, to prevent unwanted inflation by fixing a new value of money every year, and sometimes to increase the effective tax rate by taking in all the money and reissuing it at an artificially higher value.

The practice was also international. As explained in a book by Scottish economic theorist John Law in 1705, Money and Trade Considered, “Raising the [value of] money in France is laying a tax on the people,” he wrote. “When the king raises value of money from 12 livres to 14, coins are taken by the mint at 13 livres, and given out for 14. So the king gains a livre … and this tax comes to 20 or 25 million, sometimes more, according to the quantity of money. … This tax falls heavy on the poorer sort of the people.”

As an aside, Law was in France because he had killed a man in Scotland, and he caused one of the first economic bubbles in history when he tried to rescue France from its massive war debts and ended up crashing European financial markets. He fled France in 1720 and died a poor man in Venice. If you like entertaining financial stories, you should look up the Mississippi Bubble and Isaac Newton’s experience in the South Sea Bubble, both of which happened at the same time.

Centralized government control of economies is a history of failure, and inflation ravaged the entire region of Turkey, Persia, and India beginning in the late 1500s. Arriving from Europe, it was exacerbated by the Ottoman-Safavid wars and other factors. For example, Persia had no silver mines, all of her silver came from abroad, and most of it came through the borders with her sworn enemy, the Ottoman Empire. In the Ottoman Monetary Crisis of 1585, the sultan and his viziers devalued the country’s primary silver coin by 100% and reduced its silver content by 44%. Increasing amounts of silver arrived in Spain from South America, and spread to Europe and Asia. At the same time, India was Persia’s largest trading partner, but India produced much that was needed in Persia and Persia produced almost nothing needed in India. The result was a vast outflow of silver into India, and a shortage of silver in Persia, but the Dutch and English were buying less Persian silk than they had before, and after 1642 the English bought none at all. This, too, contributed to the depletion of Persia’s money supply, and the shortage caused a steady debasement of the coinage.

By 1677, French traveler Jean Chardin said, “The money itself has been altered. One no longer encounters good coins.” He also called the Indian moneylenders in Isfahan “true bloodsuckers [who] draw all the gold and silver out of the country and send it to their own,” and criticized the Persian shah for hoarding silver. Chardin referred to the Treasury as “a bottomless pit, for all is lost there and but little comes out.”

By 1684, most of the coins remaining in circulation were seriously debased, the bazaars at Isfahan were closed, and the shah ordered new money to be minted. By 1694, the population was suffering from heavy increases in taxation, a sharp decline in wealth, and a severe lack of gold and silver coin. As but one example from 1698, the manifest of one Dutch ship leaving Persia for Ceylon noted that 88.5% of her cargo consisted of European gold ducats.

Trade had been irreparably damaged. Inflation increased even further. The shah was unable to pay the army. And the famed security of Persian roads – enjoyed by our ambassadors from Holstein – disappeared as caravans were attacked even within sight of the capital.

The Safavid Empire fell in 1722.

We were supposed to hear in this episode why dogs and cats hate each other, but I hope that hearing about inflation and the great pox made up for it. We will get to that next time, and, as a bonus, you will find out why camels hate horses, on the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post