Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 30: The Most Dangerous Place in Europe.

It is the middle of April, 1638, and our German trade ministers are roughly two-thirds of the way through their 9,000-mile round-trip to Isfahan.

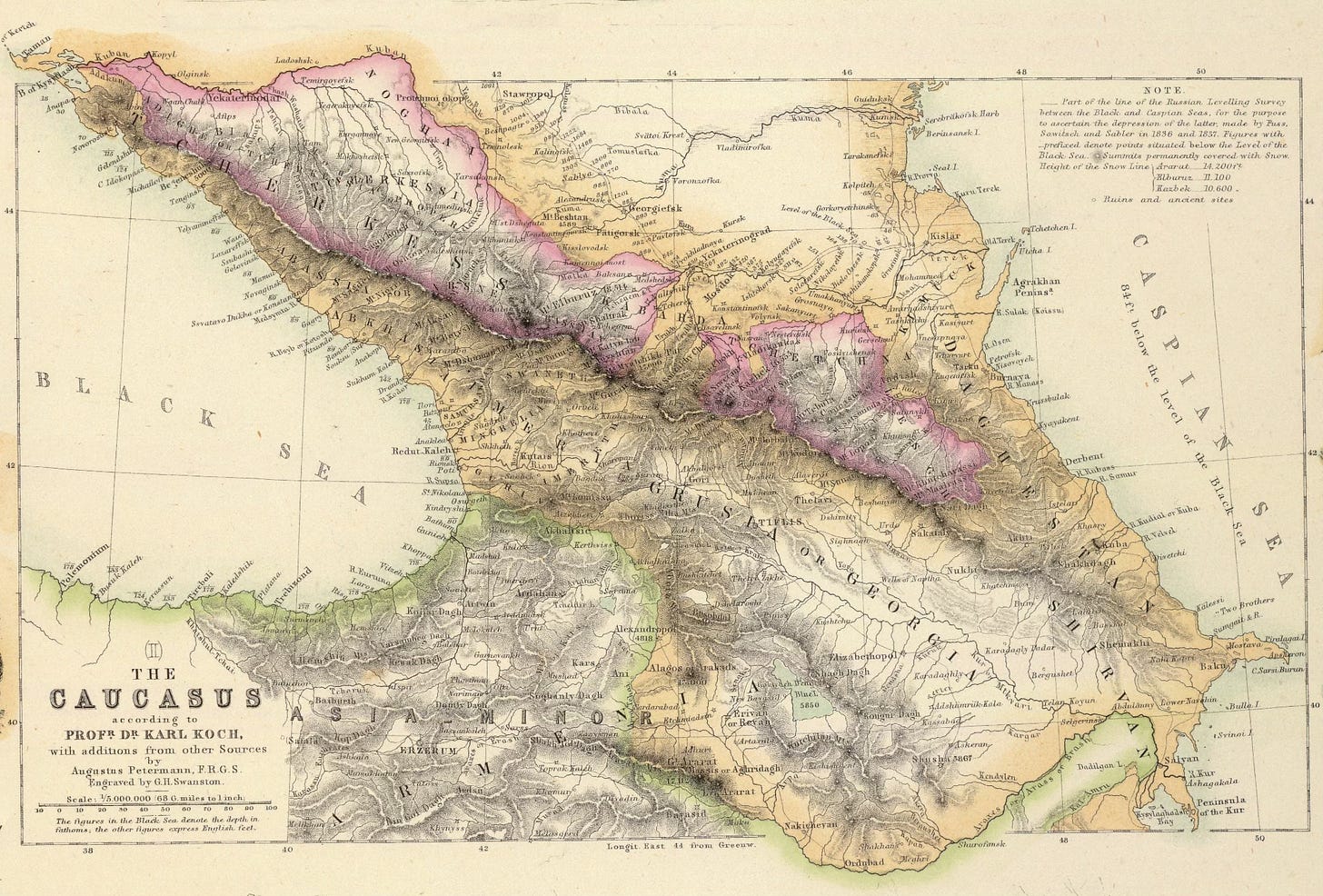

They are stuck in the city of Tarku, on the coast of the Caspian Sea, which today bears the name of Makhachkala and is the capital of Russia’s Republic of Dagestan.

They are stuck because independent warlords control every village, city, and river crossing in Dagestan, all of them have their own plans for robbing or killing the Germans, none of them want to let the other warlords get the upper hand, and none of them want to supply the Germans with the food they need to reach the Russian city of Astrakhan.

All of this makes Tarku most dangerous place of the entire journey.

As Adam Olearius tells us, “We were in greater danger there than we had been anywhere before. For during the five weeks we were among the Tartars, all they talked about was robbing, rifling, killing, and cutting throats.”

Olearius does not give us a precise timeline of events, as he has done previously. One senses a certain exhaustion in the narrative. But he does say they remain in Tarku from April 17 to May 12 and that they remain alive only by using their wits.

A messenger from one warlord tells them they will only survive if they follow his directions – because he will treat them as enemies if they don’t. The ambassadors reply that they are under the protection of the Russian Tsar and their deaths would be revenged with the greatest cruelty imaginable.

Four different warlords visit the German camp for dinner on April 20, and speak of nothing except robbing, stealing, and selling slaves. One of them complains that he had only been able to steal one girl all week.

After they leave, the Prince of Osmin’s brother comes for a visit and offers his services. Olearius does not say what those services might be, but a week earlier Osmin had threatened to kidnap the Germans on their way out of Derbent and hold them for ransom.

The mayor of Tarku arrives next, and says the Germans can expect no supplies until they send gifts to Surchou, the Khan of Tarku, so the next day they send a pair of gold bracelets, a pound of tobacco, a pistol, a firelock musket, a barrel of gunpowder, two pieces of Persian satin, and some spices. They advise the khan that he will also receive a barrel of vodka as soon as they reach their next destination.

He responds by inviting them to dinner. They decide to attend, even though they have good reason not to leave the safety of their camp, and the food is so bad it almost makes them gag. As they sit in a circle, a man in the middle carves up some meat and – if we are to believe Olearius – literally throws pieces to the guests.

“He also tore the pieces of Meat and the Fish, but all was done only by his hands, which were as black as his face; so that the fat running between his fingers, and mingling with the dirt from which it took another color, almost turned our stomachs,” Olearius writes.

Three hours of drinking and entertainment follows the meal, after which more meat – five or six pounds of sheep liver – is served by the handful and looks like it has already been chewed.

The ambassadors endure the ordeal because they must. As Olearius puts it, “there was a necessity we should comply.”

The next day, another prince invites them to dinner. His name is Iman Myrsa, he is not quite 18 years of age, and – as the nephew of Surchou Khan who usurped his throne – his life is in danger from his uncle.

The food is only slightly better than the previous night’s dinner.

“They used no knives but tore the Meat in pieces,” Olearius writes, “and I observ’d that when one had left any Meat about the bone, his next neighbor took it up and pick’d it, and many times it went to a third and fourth hand, till at last, he who could find no more meat would try to get out the marrow.”

Their dinner companions drink a sort of liquor called Bragga, which is the color of beets but made from millet – a family of small cereal grains commonly grown in Asia and Africa. Drinking out of cow’s horn cups, the barbarians drink a lot and get very drunk.

On April 23, wagons arrive in the German camp and the ambassadors prepare to leave Tarku. But multiple messages from competing warlords confuse the situation, so they send their own messenger to the Russian city of Terki – some 75 miles to the north – and ask for a military escort out of Dagestan. Their request is declined, and they become increasingly fearful for their safety.

Bad weather makes everything worse.

“The continual rains had not only sunk through our Tents and Clothes, but also hindered us from making any fire, to warm us and dress our Meat,” Olearius writes. “No condition, for misery, could be compared to that we were then in, forsaken by all, destitute of all things, even advice and resolution, insomuch that we dared not go into the Tartars huts, Surchou Khan himself having given us notice that we might run the hazard of being carried away and sold.”

On April 27, a Scotsman named William Hoye wanders a little too far from camp and is kidnapped by the Tartars. They never see him again. The same day, one of the men practicing with bows and arrows accidentally gets shot in the stomach and dies. Taking the advice of a few local Christian women, they bury his body in the horse corral and place an empty coffin in a fake grave. The Tartars, they are told, would otherwise dig up the body and feed it to their dogs.

A rich Muscovian merchant also dies, but his body is embalmed and put away until they reach the city of Terki, where it is buried in a church cemetery belonging to his religion.

On May 1, a messenger from a warlord named Sultan Mahmud offers to give them safe passage to Terki. To prove he can be trusted, he sends three of his principal lords to act as hostages.

The Germans hear – from whom, we do not know – that they can trust Mahmud, because he had atoned for his father’s sins, performed the pilgrimage to Mecca and to Muhammad’s tomb, and reformed his life.

They accept the offer, but governor Surchou Khan refuses to let them go until they offer more gifts and leave two of the hostages as a deposit for the return of the borrowed horses and oxen. They take the third hostage with them, and finally depart Tarku on May 12.

The local wagon crew hired for the 75-mile trek to Terki break their word and force ambassador Bruggeman to pay much more than originally promised. The route they take is not clear, but it most likely follows the modern E19 that heads north along the coast of the Caspian Sea.

They reach a river that Olearius does not name, which serves as the common frontier between Sultan Mahmud and the Prince of Tarku. Several Tartar lords appear on the road and ask the German doctor to visit one of their friends who is sick. The physician is afraid he will be kidnapped, so two of the Tartars stay as hostages.

At their camp on the river, dinner consists of what Olearius calls “bread and troubled water.” The doctor returns after midnight.

They make four leagues through a thickly-forested country the next day. The Muscovian Ambassador traveling with them beats one of the wagon crew along the way. The crew threatens to leave them in the wilderness, and relents only after much pleading.

They go without dinner, spend the night in the forest, and reach the river Koisu early the next day. The town of Andre sits on a hill near the river, where fishing is the primary business.

“The inhabitants are for the most part fishermen,” Olearius writes, “and we saw them in great numbers upon the River-side, about their employment. They thrust a sharp hook baited, which is fasten’d to a long pole, to the bottom of the river, and by that means take abundance of sturgeons, and such like fish.”

He also hears of an odd wedding custom, by which all the men in attendance shoot an arrow into the floor and leave them there until they rot or fall over. But he never could learn the reason for it.

The river is “thick and troubled, and its course very swift,” Olearius tells us, “at least as broad as the Elbe and in that place it was above twenty foot deep.”

The Germans have 70 wagons that must cross the river, and the fishermen sense a business opportunity. They propose joining two boats together, topping them with heavy planks to make a bridge, and charging two crowns for each wagon.

Ambassador Bruggeman bargains with them, proposing one price for all the wagons. The locals respond, as Olearius puts it, by retiring to the other side of the river and “jeering and laughing at us.”

The Schemkal of the town of Andre arrives with a great number of mounted soldiers, adding fear and uncertainty to frustration. Fortunately, he does nothing but observe.

The town that Olearius calls Andre appears on various 18th century maps as St. Andrea, Androw, Andreof, or Andru, is located in a region named Lazghi.

There is no town of that name on any modern map I can find, but the Universal Geography of 1827 – written by the Danish-French geographer Conrad Malte-Brun – mentions that the market town of Endery is where “the Lesghians sell their plunder.”

The 1911 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica says Lesghian (from the Persian Leksi) is the name for “a number of tribes in the eastern Caucasus, who, with their kinsfolk the Chechens, have inhabited Dagestan from time immemorial.”

There were 27 total tribes of Lesghians in the 1800’s, each of which spoke a different dialect. Intelligent, bold and persistent, and capable of reckless bravery, says Britannica, they were capable of enduring great physical fatigue and lived a semi-savage life in the Caucasus, subsisting by hunting and stock-breeding. They were, for the most part, fanatical Muslims, and were forced to become Russian subjects in 1859.

All of that rings true, based on everything else we’ve heard about the Dagestan barbarians. The Germans cannot wait to escape their predicament, but they are forced to camp on the riverside that night, making crude huts out of tree branches.

Olearius and the other literate men dine with Ambassador Crusius, and it appears that they have run out of alcohol, for they are forced to drink oxicrat, a beverage of vinegar and water.

Turning their abject reality into poetic license, Olearius writes that the drink was “increas’d by the tears we shed, reflecting on the difference there was, between our present condition and that we should be in at our return into our dear country.”

The Germans are literally crying in their beer.

They cross the river the next day, thanks to the Russian ambassador who negotiates a price of 40 crowns – instead of 140 – for the passage of all the company and the baggage. With the Schemkal and his armed men lurking in the area, Bruggeman immediately orders them to make camp and man the guns. Which is a prudent decision, for 50 of the barbarians arrive shortly thereafter.

The lord is about 36 years of age, strong, bulky, and handsome. He is wearing a coarse cloak over a coat of green satin and a shirt of mail armor, and is armed with a scimitar, bow, and arrows.

The visitors bring food. Aside from sheep and lamb, they set a cauldron on the fire to boil. It is full of sturgeon cut into little pieces, boiled in water and salt and served with a sauce of fresh butter and sorrel. Native to Eurasia, sorrel is a perennial herb that has a lemony flavor, and is collected in the springtime, dried, and added to soups and stews.

Olearius tells us he “never had a better meal,” and “all the delicates of Persia were not comparable to that dish.”

They drink vodka and play music after dinner, shoot the cannons a few times, and then give the Schemkal the usual kinds of gifts: gold bracelets, a silver goblet, a scarlet cloak lined with fur, two pistols, a sword, a barrel of gunpowder, Persian silk, and some leather goatskins.

The lord immediately puts on the cloak and gives his own to Ambassador Bruggeman, who has the sense to accept.

Bruggeman tells the story of their journey, and says they will be returning through Dagestan once a year to trade with the Persians. The lie is followed by flattery. Dagestan is a country unknown to the Duke of Holstein, but if he had known Bruggeman would meet with so great a lord, he would have sent even greater gifts and made a perpetual friendship with the Schemkal.

The barbarian lord is so pleased with the evening that he provides horses, saddles, and a carriage for the rest of the trip to Terki.

They cross four more rivers over the next three days, and the peaks of the Caucasus begin to recede in the distance behind them. The River Bustro marks the frontier between Dagestan and Circassia, beyond which the wagoneers of Tarku will not travel, and the Germans are much relieved after the crossing.

“We cross’d the river, and got over the Baggage, to our greater satisfaction in this particular,” Olearius writes. “That we left on the other side of the river the Muslims and Pagans, and were entered into Christendom.”

Unfortunately, the region is infested with snakes, more than six feet long and as large around as a man’s arm. At night, the serpents retreat into large holes in the ground, but during the day they “sport themselves in the heat of the sun.”

The snakes eat a species of field mouse peculiar to the region. They have heads and tails like rats, their hair is black, and they have short front legs and long hind legs. Thus, they cannot run very fast, but they can jump up to six feet into the air, and the Germans enjoy shooting them, especially when many of them jump up at the same time.

The Bustro appears on maps from the 1700’s, but has since disappeared, possibly diverted into the man-made canals that crisscross the region. Likewise, the city of Terki no longer exists on the banks of the Terek River, which Olearius calls the River Timenski.

The mouth of the Terek is one of the largest river deltas in southern Russia, comprising some 8,000 square miles of irrigated farms and cattle ranches. In 2002, a massive flood wiped out vast numbers of homes, farms, bridges, levees and dams. Similar floods occurred in 1937 and 1967, and the river appears to have changed course since the Bruggeman mission passed through.

Although we don’t know the exact location of Terki, we spent some time there in episode 8, and it was described as a wooden fortress about two miles from the Caspian Sea, garrisoned by 1500 Russian soldiers and recently improved with earthwork ramparts and bastions.

The crew of the Friedrich had staged a mutiny in Terki, led by a sail-maker named Anthony Manson. The ambassadors had condemned him to prison until the return trip from Persia, but now that the Germans have returned there is no mention of Mr. Manson.

They arrive in Terki on May 20. Tents are pitched outside the city, where they are treated to gingerbread, alcohol, and Christian hospitality. A few days later they dine with Princess Bika, the mother of the local prince.

“Now was our joy complete,” Olearius writes, “to find ourselves out of the power of the Tartars of Dagestan, and among the Muscovites, who were our friends and acquaintances, which made us send for our Musick to divert ourselves at Prince Mussal’s court.”

Olearius had promised us a description of the Circassian Tartars in Book 4, but events forced them to travel by sea instead of land, bypassing the region and being shipwrecked in Dagestan. He makes good on that promise now, and disputes the claim of Joseph Justus Scaliger that the Circassian Tartars are “the most perfidious and most barbarous of any nation.”

That claim, Olearius says, is more true of the barbarians of Dagestan, for the Circassians are somewhat less barbarous, and more compliant. This is undoubtedly because they are subject to the jurisdiction of the Russian Tsar. After years of living among the Christians, he says, they did, by degrees, quit their former barbarism.

Scaliger (1540-1609) was a Dutch linguist and historian who studied in Bordeaux and Paris, traveled to all the great universities in France, Germany and Italy, taught at an academy in Geneva, and ended his career at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. Britannica says he was the most erudite scholar of his time, but as we have seen before, Olearius has no qualms about correcting the experts of the past.

The city of Terki is the great metropolis of the region, and all the Circassian towns are governed by the Tsar, to whom the lords of the country have pledged allegiance.

Although modern maps locate Circassia at the western end of the Caucasus near the Black Sea, Olearius clearly uses the term to describe a larger region between the Black Sea and the Caspian.

They are believed to be descendants of the Hatti people who lived in Anatolia around 3000 BC, and were forced out when the Hittites invaded a thousand years later. They migrated north and built a civilization in the Caucasus, which the Mongols destroyed in the 13th century, and they had been under the control of larger powers for centuries – the Greeks, Romans, Mongols, Crimean Tatars, Turks, etc.

In 1638 they are largely Sunni Muslims allied with the Tsar to gain protection from repeated Persian and Turkish invasions. As we have seen in previous episodes, the Persians kidnapped tens of thousands of people from the Caucasus regions and made them slaves of the empire.

There may have been close to two million Circassians alive when Peter the Great declared the region a Russian province in 1785. In the wars that followed between Russia, Persia, and Turkey, the Circassians fiercely resisted the Russians but finally succumbed in 1860, when Tsar Alexander II forcibly relocated them to a smaller region closer to the Black Sea.

Rather than live under the Tsar’s rule, some 400,000 people crossed the border into the Ottoman Empire and thousands died of starvation and disease on the way. Some sources say up to a million were killed in the Circassian genocide of 1864.

Olearius says their houses are poor, built mostly of earth and tree branches on the outside, the inside walls plastered with clay.

“The men, for the most part, are strong, and of yellowish complexion,” he writes. “Their hair is black and long, save that they shave the midst of their heads, from their forehead to the neck, about the breadth of an inch, leaving at the crown a little lock, which falls down behind.”

Their women are what Olearius calls “well shaped,” with “good faces” that are never covered, “a clear and smooth complexion, and cheeks well colored.”

Their hair is black, and hangs in two braids on both sides of their heads. The widows wear an inflated ox bladder behind their necks, covered with cotton fabric in a variety of colors, and at a distance they seem to have two heads. In summer they wear only a smock, dyed red, green, yellow, or blue and cut down the front that a man may see down to their navels.

Four such women come to visit the day after their arrival, and Olearius calls them “very familiar and of a very good humour.” They stay until they have exhausted their curiosity, and they even allow the German men – who pretend to examine the copper necklaces and amber beads –to “slip their hands down into their bosoms.”

Some of the women invite the Germans into their homes while their men are working the fields, but their behavior is described to Olearius as a “miracle of chastity.”

A German military officer says he visits the home of one beautiful woman who makes him a handkerchief, washes his hair, and does anything he asks – except be unfaithful to her husband. As she tells him, the husbands have confidence in their wives and the wives return that with their honesty. It is lawful for a man to marry several wives, but most content themselves with one.

To express sorrow for the death of a friend, they tear their forehead, arms, and breasts, with their nails so that the blood flows in abundance. Mourning continues until the wounds are healed, but if they would have it last longer then they reopen the wounds in the same manner.

When a person of quality dies, the family and friends sacrifice a male goat. To see if an animal is fit for the sacrifice, they cut of its genitals and throw them against the wall. If they do not stick on the wall, they choose a different animal. If they do stick, the goat’s skin is stretched on the top of a long pole. The meat is offered as a sacrifice, then boiled, roasted, and eaten. The women go home after the feast. The men pray in front of the stretched skin and then get so drunk that they usually end up fighting. The skin is left on the pole in a place where dogs cannot piss upon it. When another person of quality dies, the old skin is taken down and the ritual is repeated.

On May 21, a caravan of merchants – Persians, Turks, Greeks, Armenians, and Muscovites – arrives in Terki. They make plans to travel with the Germans to Astrakhan, and together they have more than 200 wagons.

For some reason, the provisions for the 200-mile trip are scant. Each man gets only of a loaf of moldy brown bread, half a dried salmon that stinks, and nothing to drink. The Circassians insist that they had made travel arrangements only for the men, not for any supplies, and so they refuse to allow any barrels onto the wagons. Bruggeman, who could take charge of a wagon to carry beer or water for the Germans, decides not to do so, although he does provide supplies for himself and his favorites.

Olearius says the rest of the members are not much bothered by the decision, because their maps tell them it is impossible they should go without water.

With ominous foreshadowing, he says they “had time enough to repent us of that presumption.”

The caravan leaves Terki on the afternoon of June 4, 1638, and enters what Olearius calls “a dreadful heath” – the Volga delta – that stretches all the way to Astrakhan.

“’Tis a thing strange, yet very certain,” Olearius writes, “that, in eleven days journey we saw neither city nor Village, nor tree, nor hill … not so much as one bird, but only a vast Plain, desert, sandy, and cover’d in some places with a little grass, and pits or standing pools of salt or corrupt and stinking water.”

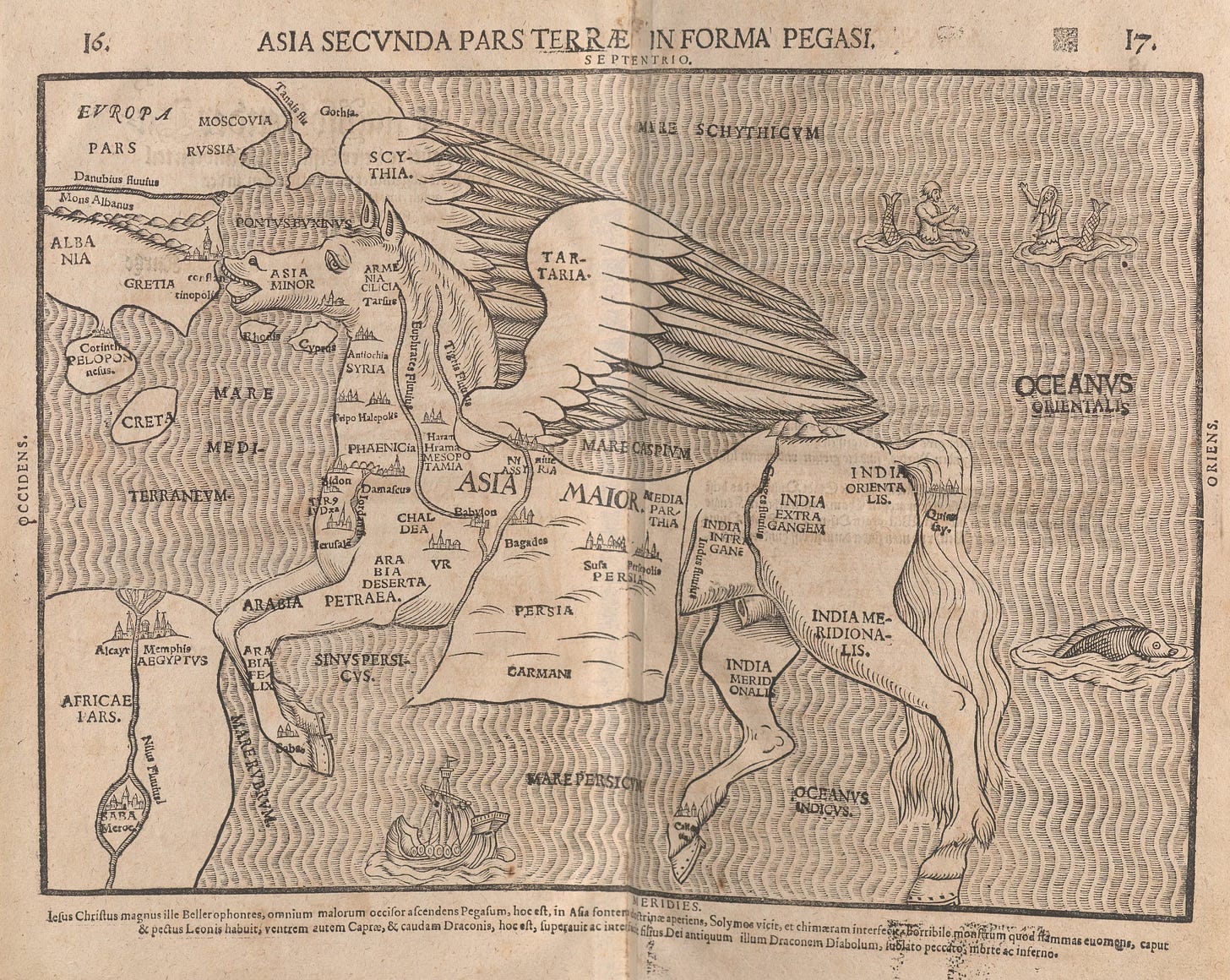

Their maps, which represent something quite to the contrary, are wrong. We don’t know what maps the Germans are using, but the 1730 map by Guillaume de L’Isle calls it “the ponds that overflow from the sea,” and the 1747 map by Emanuel Bowen calls it a great salt lake.

They spend the first night near one of those pools of standing water, and the next near the River Kisilar, the last river until they reach the Volga.

On June 7 they struggle for six leagues through a vast fen.

“Heat and thirst troubled us extremely,” he writes, “but not so much as the Flies, Wasps, Gnats, and other infects, which both men and horses found it no small difficulty to keep off. The Camels, which have no tails, to keep away those infects, as the horses have, were all bloody, and full of swellings.”

On the night of June 8, the Tartars kill one of their horses, roast the meat over a fire, and are very merry. They do not share with the Germans.

They find water on June 9, but it is so bad that they hold their noses while drinking it. The next day they make another seven leagues to a place covered with reeds, with a little fresh water that comes from the Volga.

The water they find on June 11 is not salt, but is so dead and stinking that they cannot drink it. Sometime that day, twelve wild boars cross their path and several Tartars horsemen ride out in pursuit. Horses pulling several of the wagons become frightened and start running. The German physician and steward fall out of their wagon along with the baggage. Olearius is near the front of his wagon and manages to hold on until the horses encounter a marsh and stop running.

Bu June 13 they can see Astrakhan in the distance, and by the 14th they reach the Volga.

“All our people, who had not drunk any fresh water since their coming from Terki, ran up to their knees in the River,” Olearius writes, “to drink with greater ease.”

They cross the river on June 15. Outside the city gates, a storehouse full of provisions is waiting for them, having been delivered from Moscow six months earlier.

In addition to suffering from biting flies and lack of water, no one has changed clothes for 11 days, but Ambassador Bruggeman orders all the baggage to be seized and searched for contraband. The exasperated men become enraged, and, disobeying Bruggeman’s orders, break into the room where the luggage is stored and carry it away.

In the next episode, the weary Germans spend three months in Astrakhan without speaking to Bruggeman, they discover him making plans to abandon the mission, and we find out what they do with two young kidnapped girls who have been sold to them by Russian soldiers, in the final installment of the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post