Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 29: Barbarians of Dagestan.

Our ambassadors leave the city of Schamachie on March 30, 1638, keeping an eye out for highway robbers, and a week later arrive in Derbent. Our author, Adam Olearius, says little about this 100-mile leg of the journey, having traveled over much the same ground after being shipwrecked nearby a year and a half earlier.

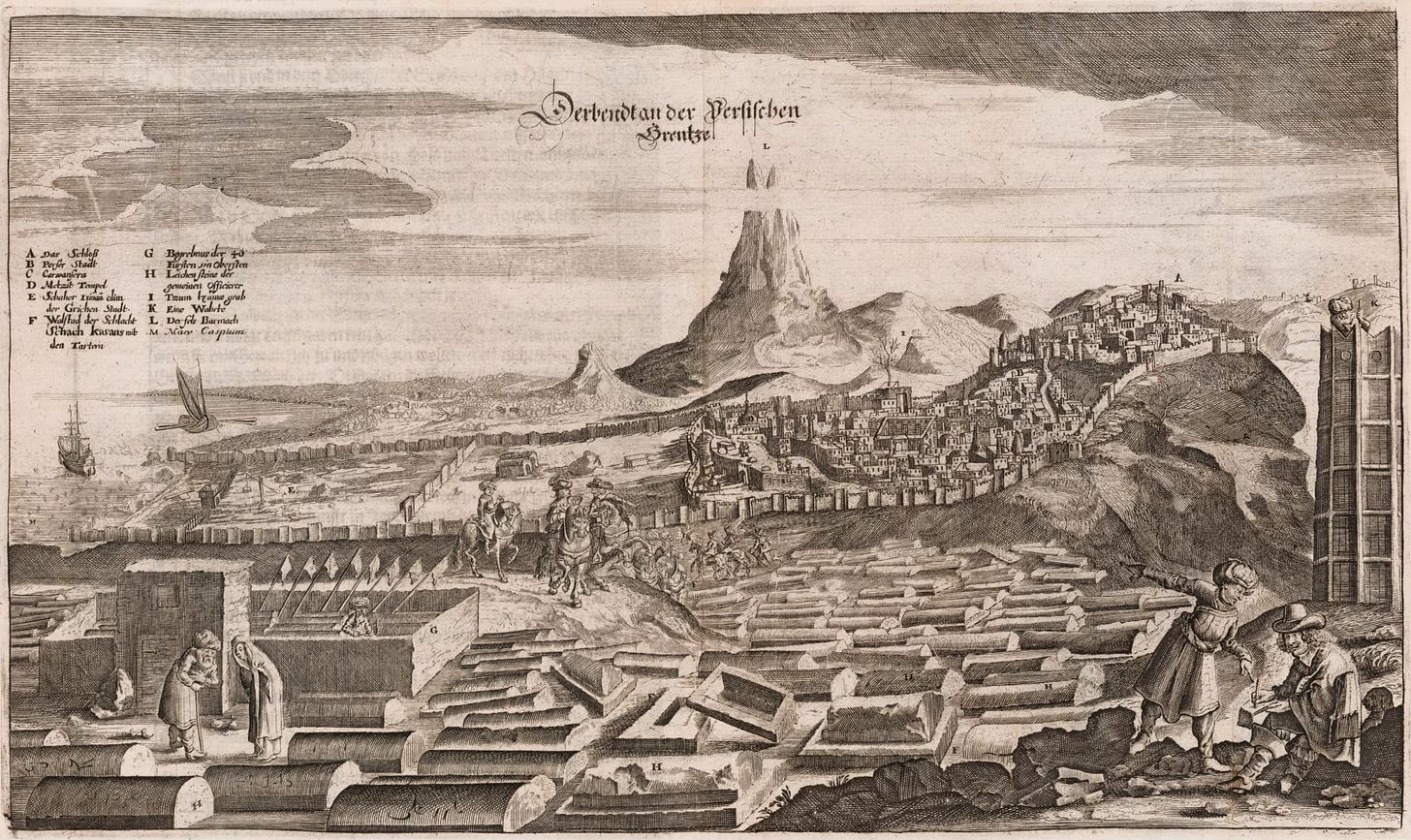

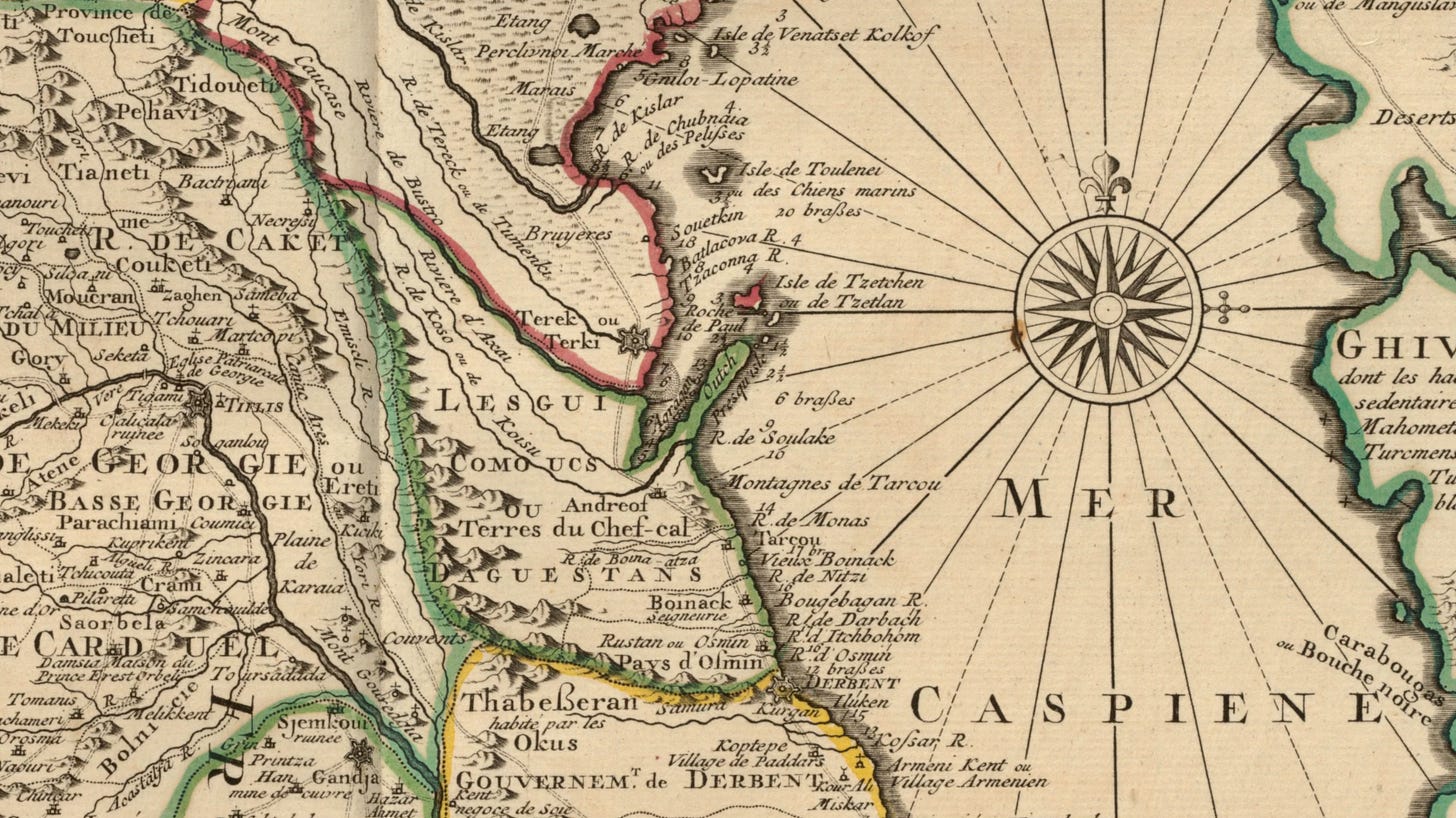

The coastline of Derbent is pure rock, and serves as the foundation of the city wall, which is so broad that a wagon easily be driven on top of it. The city is sometimes called the Gate of Persia, since it lies on the extreme northwestern edge of the empire, and its walls extends from the sea to the top of a nearby mountain.

The mountain above the city is covered with trees, and Olearius can still see the ruins of a wall, once more than fifty leagues in length, that was part of a communications network between the Caspian and the Black Sea. One German league is 4.6 English miles, so Olearius is telling us the wall was 230 miles long.

The wall is five or six feet high in some places and completely destroyed in others. Two mountain castles still house garrisons of soldiers, while other structures were destroyed long ago.

The remains of the fortress can still be seen today, and they were once part of a truly huge defensive complex erected by the Sassanid king Khosrow I sometime between 560 and 570 AD. You will remember from episode 9 that the Sasanians replaced the Parthians in 224 AD, thus becoming the last pre-Islamic Persian empire and achieving what is considered to be the high-water mark of Persian culture. The Muslims replaced the Sassanid Persians in 651 AD.

The drawing of Derbent by Olearius shows two parallel city walls that begin in the sea, creating a harbor for ships. Modern sources say the walls extended some 500 feet into the sea. About two miles inland, they encompass the mountain fortress, but the walls are less than a half mile apart, and the total area of the old city appears to be quite small.

Another wall in the distance disappears over the mountain, and – if we believe our intrepid author – stretches west for 230 miles, which, as the crow flies, is about the distance from Derbent to the city of Erivan.

This long defensive wall is known as Dagh Bary, which literally means “Mountain Wall” from the Turkish word for mountain and the Persian word for wall. According to the Encyclopedia Iranica, it stretched “many kilometers” into the mountains and had numerous fortresses and towers of its own.

It is also called Alexander’s Wall because legend has it that Alexander the Great built the wall to defend against the tribes of Gog and Magog to the north.

Olearius correctly tells us that Persian authors say the wall was built by Alexander, but that is not the whole story. Among others, Persian poet Neẓāmī Ganjavī (1141-1209 AD) advanced this narrative in his poetical version of the life of Alexander. Flemish Franciscan missionary William of Rubruck, who traveled extensively throughout the region between 1253 and 1255, brought the legend back to Europe. And in the 1560s, English merchant Anthony Jenkinson saw the ruins of Dagh Bary and heard that Alexander had built it.

As we heard in episode 8, Jenkinson began his career as an agent of the Russia Company, bought a Tatar slave girl in Astrakhan for England’s Queen Elizabeth, and also carried Elizabeth’s letters to the second Safavid shah in 1561.

As late as 1841, the people of Derbent still believed the wall was built by Alexander. At least, that’s what we’re told by Abbasgulu Bakikhanov, a 19th-century Tatar genius who served the Russian Empire and wrote a Persian-language chronicle on the history of Shirvan, Dagestan, and Derbent.

But that is not the only myth about Derbent’s defenses, because legend has it that the so-called Day of Judgment Gate constructed in the 10th to 11th centuries is a portal to another world. Medieval Islamic mystics said that – if you listen closely – the voice of Allah can be heard there.

Arabic inscriptions on one of the Dagh Bary fortresses dates to 792 AD and identifies Khosrow I as the builder. Eventually, some 60 fortresses were built along the wall, and modern archaeological evidence puts its final length at just 27 miles, a far cry from the 230 miles quoted by Olearius.

The defenses were occupied from the 6th to the beginning of the 13th centuries, and were abandoned after the arrival of Mongol invaders. The structures decayed over the centuries, and regional authorities actively demolished many of them during the 19th and 20th centuries.

After years of war between Persia and Russia, Derbent was conquered by Tsar Alexander I in 1813. You can visit the remains of the fortress, which is now called Naryn-Kala. The citadel, the ancient city, and its defensive walls were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.

If Olearius knows that Allah’s voice can be heard at the Day of Judgment Gate, he doesn’t mention it. In fact, the fortress isn’t even the most remarkable thing about the city of Derbent. That, Olearius insists, is the Sepulchre of Tzumtzume.

The sepulchre is mentioned in a poem by Mehmed bin Süleyman Fuzuli, an Azerbaijani poet whose patrons included the Safavid governor of Baghdad.

Born around the year 1495 in what is now the Iraqi city of Karbala (or possibly in the city of Najaf), Fuzuli wrote poetry in three languages – Persian, Arabic, and the Azerbaijani dialect of Turkish – died during a plague outbreak in Karbala in 1556, and became known as the most outstanding figure in the classical school of Turkish literature.

The poem referred to by Olearius says that Jesus Christ had once traveled in the area, and stumbled on a dead man’s skull in the road.

Wanting to know whose skull it was, he prayed to God – with whom he was in great favor, of course – that the dead man should be made alive again. Which God accordingly did.

Jesus asked him who he was. He replied that his name was Tzumtzume, and that he had been king of the country. He was so powerful that every day he consumed as much salt as forty camels were able to carry, and not only did he have 40,000 cooks, but he also had just as many musicians, just as many pages with pearls in their ears, and just as many servants.

After this, Tzumtzume asked Jesus who he was, and what religion he professed. Jesus gave his name and said his religion was that which saves all the world.

If that’s true, replied Tzumtzume, then I am of the same religion, but I ask you to let me die again as soon as possible because, having once been so powerful, it would be nothing but trouble to live without my kingdom and subjects.

Jesus granted his wish, Tzumtzume died immediately, and on that place his sepulchre, ten feet high and sixteen feet square, was built under a great tree.

Nearby, as Olearius depicts in his drawing of Derbent, there are five or six thousand more tombs, cylindrical and hollow inside, covered with Arabic inscriptions. It is a military cemetery for officers killed in a battle against the Tartars of Dagestan. Another 40 tombs, much bigger and surrounded by a wall, belong to the many great lords and holy persons who had been killed in the same battle. The cemetery is attended by an old poor man who lives only on the alms that are given to him.

Olearius does not dispute the story of Jesus and Tzumtzume, as he has done with other myths, and I cannot find any information about a Persian king of that name. The only similar word I can find is Tzimtzum, a word from the mystical Jewish tradition of Kabbalah that describes “a reduction of the divine energy that creates worlds.”

I won’t try to explain it beyond that, but it could be that King Tzumtzume is just a poetical allegory for the Kabbalistic concept of Tzimtzum. After all, one of Fuzuli’s most famous works is a rendition of a great Muslim allegorical romance that depicts how the human spirit is attracted to divine beauty. During the Islamic Golden Age from the 8th to the 13th centuries, Sufi Muslim thinkers often exchanged ideas with Jewish and Christian mystics, and the Safavid dynasty was founded by a Sufi mystic.

On the other hand, it could be that Olearius mistakenly attributed the story to Fuzuli, or got the story from local folklore.

All I know for sure is that we’ll probably never know for sure.

On April 13, 1638, the Germans see several Tatars, men and women, perform devotions at the 40 tombs. There are no Christians in Derbent, only Muslims and a few Jews, and according to Olearius the only business in the city is the trade of children stolen from Muscovy.

We discussed the Islamic slave trade in episode 5, when Olearius wrote that the Tatars appear to do little except kidnap the Russian Tsar’s subjects and sell them in Ottoman and Persian slave markets. The slave trade began in the 1200’s and focused largely on the steppes of Ukraine and Russia north of the Black Sea. Ottoman sultans frequently sponsored slave raids and even had a word for the practice – slaves were a “blood tax” owed to the empire.

The soldiers and citizens of Derbent are “a proud, daring, and insolent sort of people,” Olearius tells us, “so far from treating us with any civility, that, on the contrary, they did what they could to pick a quarrel with us.”

This seems a bit rich given what we know about the behavior of the Germans, but their Persian guide nevertheless advises them to post armed guards in case violence breaks out. And an order comes down from the ambassadors – Olearius does not say if it originated with Bruggeman – that no one should tempt any citizen of Derbent, either in word or deed, to quarrel with them, lest the locals fall upon the whole company and murder them. This, as we have recently seen, is a very real possibility.

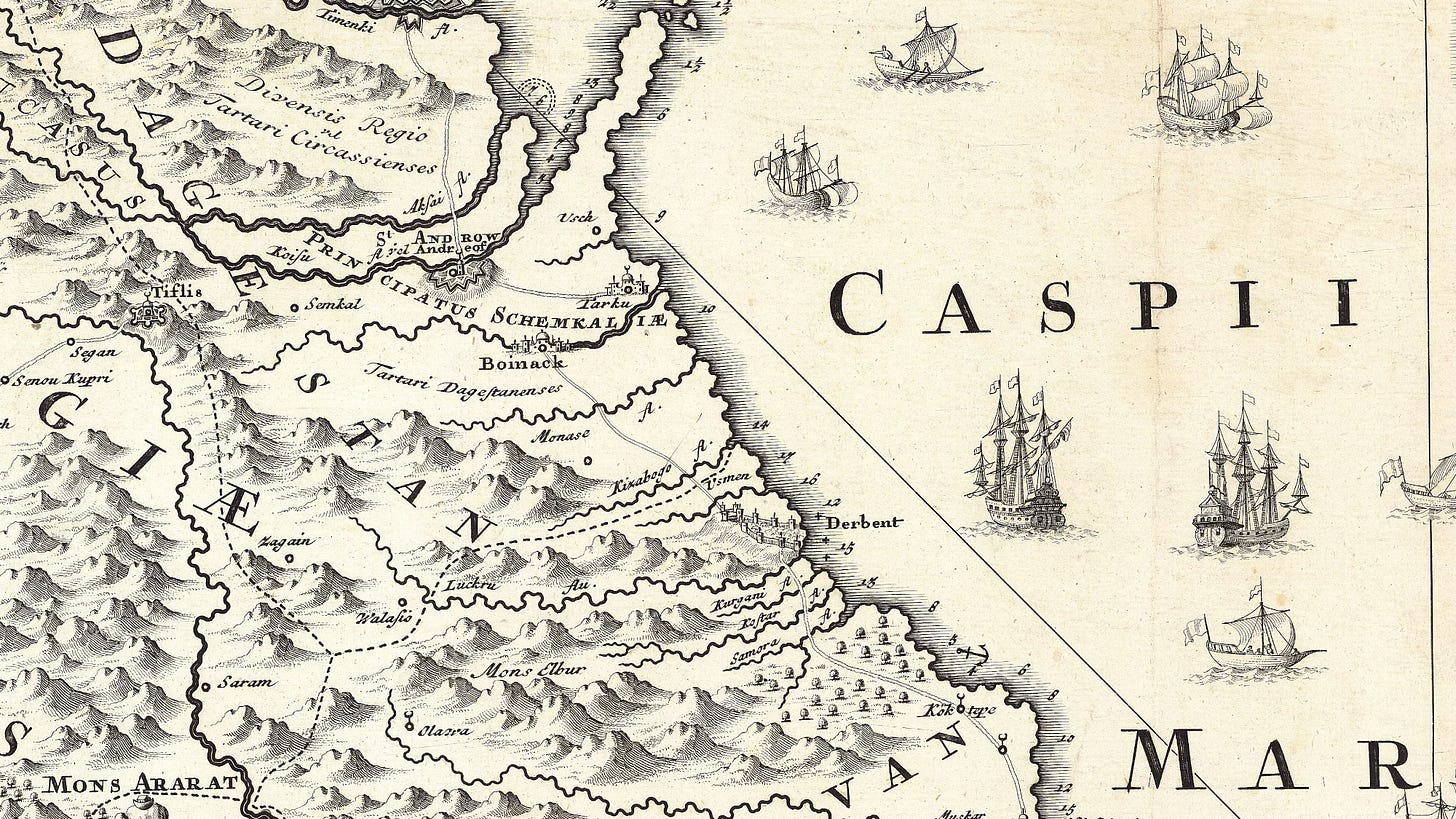

They are eager to leave Derbent, but wary of the route. Their next stop – the city of Tarku – lies across the border in the dangerous province of Dagestan.

Olearius writes: “The khan of Tarku, who had given the Ambassadors a visit at their former passage that way, sent us word that the way we were to travel through the Country of the Tartars of Dagesthan, was very dangerous, desiring us to make use of the Convoy he proffered us. The Ambassadors, considering that those proffers were made by a Tartar of Dagesthan, and that there were no more safety in his Company than among the Robbers themselves, returned him their thanks, and sent him word, that they would not put him to that trouble.”

So before leaving, the ambassadors take stock of their weapons, counting 52 muskets and firelocks, 19 cases of pistols, two brass cannons, and four murdering-pieces (the stone-firing cannons), all fit for service. They also distribute four days’ worth of food to everyone, anticipating that no provisions will be available during the 70-mile journey to Tarku.

They mount up on April 13, only to discover that the governor of Derbent has shut the city gate.

“This news somewhat startled us, and oblig’d the Ambassadors to send the guide to know the reason,” Olearius writes. “His answer was, that, having received intelligence, that Osmin, a Tartar-Prince, not far from Derbent, intended to set upon us by the way, and put us to an excessive ransom, or take away all we had, and that being responsible to the King for what might happen to us, he thought it not fit we should go thence without a Convoy, which being not to be had that day, he desired us to stay till the next.”

They agree to stay one more night, but insist on camping a mile outside the city, near a vineyard on the side of a small river that serves as the border between the Tartars of Dagestan and the Persians.

The convoy promised by the governor never arrives, so the Germans leave on April 14, and the advance guard of soldiers carry their firelock muskets lit and ready for action. The weapons are also called matchlocks, and they use a piece of burning cord to ignite the gunpowder.

The cannon, murdering pieces, and a supply wagon are next, followed by camels loaded with the baggage, with Ambassador Crusius in command.

Another cannon follows the baggage, and Ambassador Bruggeman brings up the rear with the rest of the company.

In this order they leave the frontiers of Persia and march into the land of the Tartars of Dagestan.

“The Inhabitants are of a yellowish and dark complexion, inclining to black,” Olearius tells us. “They are well set and have strong limbs, dreadfully ugly in their faces, and wear their hair, which is black and greasy, falling down over their shoulders. They are all barbarous and savages.”

Their clothing consists of a sheepskin cloak worn over a long coat, grey or black in color, made of wretched coarse cloth. On their heads they wear a square cap, and their leather shoes are made of sheepskin or horse hide.

The men are circumcised and follow the Islamic religious ceremonies of the Turks, but Olearius says they are “so slenderly instructed therein, that it is not to be wondered, they have so little devotion.”

While the women herd cattle, the Tatar men “go up and down a-robbing, making no conscience to steal away the children of their nearest relations, to sell them to the Persians and others.” The natural consequence of this is that the Tatars live in perpetual distrust of one another.

When they capture traveling merchants, the Tatar men hold them for ransom, so that any caravans which do not go by sea are heavily armed. The highwaymen fear neither the Persians nor the Muscovites because no army is able to follow them into the mountains, where they retreat when they are pursued.

Dagestan is subject to no single ruler. Instead, every city has its own lord who bears the title of Schemkal. Olearius describes the manner in which this man is elected: “Upon the death of the Schemkal, the other Lords meet, and sit down in a ring, into which the local Priest throws a golden Apple. The person who is first touched by the apple is made Schemkal.” But his power is not absolute, for the other lords give him only a certain amount of respect and compliance, and that is not very great.

After traveling five leagues, or about 23 miles, the German caravan arrives at the village of Rustain, which was also the name of the ruling Schemkal. He sends his son to meet the ambassadors, attended by 15 well-armed men on horseback. After a brief exchange of compliments, the Tatars disappear into the woods and the Germans make camp in an open field and post sentries to guard against any surprise raids.

The young prince named Rustain makes an appearance in the camp that evening, but meets only with the Muscovian ambassador and, Olearius tells us, only to learn about who the Germans are and what goods might be stolen from them.

“We intended him a present of 12 ducats, and three pieces of Persia-Satin, had he honored the Ambassadors with a visit; but he thought it enough to do it by two of his Officers, whereupon we only saluted him with the firing of two great Guns, charg’d with bullets, just at his departure from the Muscovian Ambassador.”

They continue their journey the next day, make camp in hilly country 30 miles up the coast, and fortify the camp with the baggage. The local village folk come for a look-see, and ambassador Bruggeman gets so angry that he orders a volley to be fired from unloaded muskets. None of the soldiers will obey his command, for fear that the villagers will respond with mass murder.

The situation worsens as the villagers who are “wicked and daring” tell the Germans that they are camped on ground that does not belong to them.

“They cared for neither the King of Persia nor Duke of Muscovy,” Olearius writes. “They were Dagasthans, and acknowledg’d no Superiour but God. They would not, at first, suffer us to go for water without paying for it; but finding that the well was within the reach of our great Guns, and that we set things in order to force our way to it, they retreated and left us.”

The Schemkal of the town sends word that the Germans may not leave until he has searched the baggage for any trade goods. The ambassadors send a reply, first that they are not merchants and may pass through without paying taxes, and second that if he offers to do violence the Germans will do what nature demands to prevent it. They hear no more from him, but Olearius recounts that a Polish Ambassador had once stayed in the same village, had argued with the villagers, had been murdered, and that only three of his servants survived.

They depart the village on April 16, arriving before nightfall in the territory belonging to the Prince of Tarku. Here, Olearius himself narrowly escapes being captured by Tatar barbarians.

“Hearing that we were not above a quarter of a league from the Sea-side, I left the Company, taking along with me the Master’s Mate, Cornelius Nicholson, to go and observe the situation thereof: but we were hardly got thither, ere we discover’d at a distance two Tartars, follow’d, within two or three hundred paces, by eight more, who, as soon as they perceiv’d us, made all the haste they could towards us; but we soon recover’d the Road. The two first seeing us retreat, pursu’d us in full speed, with their Javelins in their hands; till the other eight, doubting, it seems, that we might not be alone in those parts, got up to a hill, to take a view of the Country, and seeing all our Company, from which we could not be above a Musket-shot distant, they call’d to the other two, to give them notice it was in vain to pursue us. Whereupon, they rode on gently, and came all together to the Company, saluted it, admir’d our Cloaths, and would needs see our Pistols, but were not permitted to handle them.”

They make camp outside the city of Tarku, near a spring that is only a mile from the sea. Located in the mountains where the rock is hard as flint, there are still good pastures and several freshwater streams fall from the hills into the city.

Tarku has no walls, but it is nevertheless “the Metropolis of all Dagesthan” and might even contain a thousand houses, built according to the Persian way but not as well.

Like the rest of the Tatars, the inhabitants of Tarku are barbarous and mischievous, but the women and maids are more civil. They do not cover their faces, and they are not as socially constrained as the Persian women.

“The maids have their hair tied up in forty tresses,” Olearius writes, “which hang down about their heads, and they were not shy of being seen, nor of having their hair felt.”

There is an old German man named Matthias Magmar living in Tarku. Born in Ottingen – located roughly between Hamburg and Hannover – he was once a weaver who fought the Turks in Hungary, was captured, and eventually sold as a slave to the Tatars of Turku. He is circumcised, and has almost forgotten the German language, but he tells the ambassadors he is a Christian who believes in the one God who is three persons and he recites the Lord’s Prayer for them with gusto.

The Khan of Tarku is named Surchou, he is about 38 years of age, and he pretends to be descended from the Kings of Persia. He does, however, maintain good relations with Shah Safi, so that when Dagestan goes to war the Shah sends troops. He wields considerable, but not absolute, authority, and his nephew offers our ambassadors both friendship and service that make them confident of their safety in the city.

The Germans do not feel safe on the road, and so they ask their Persian guide to stay and lead them to the next destination, the city of Terki that lies on the border with Muscovy. The guide declines, saying he has express orders to take them no further then Tarku, and that his life will be in danger if he disobeys.

There is some confusion about precisely where the Germans are, because Olearius clearly distinguishes between Tarku and Terki, his book contains illustrations of each, and yet there is no modern city of Terki. There is, however, a Russian city named Tarki that is in the Republic of Dagestan and was formerly known as Tarkou or Tarku.

No matter where they are, their lives are in danger, and so they ask their Persian guide if he can at least leave them the wagons, the camels, and the camel drivers. He agrees, and then leaves in the middle of the night.

Olearius writes: “This sudden departure of his startled us the more, in that, the next day, two women, who sold us milk, and pretended to be Muscovites, and Christians, and that they had been stolen away in their youth, and married in that Country, came to tell us, that the Tartars intended to kill us all, out of an imagination that we carried along with us a vast treasure.”

The women also say that Surkou has been told they did not pay the required taxes in several villages they passed through, that they had threatened the people of those villages, and that the Schemkals of those villages have resolved to attack the Germans, kill all the old people, and make the rest of them slaves.

They don’t know whether to trust the report, but sentries notice Tatar activity that seems to portent what Olearius calls “the execution of some great design.”

The ambassadors call an emergency meeting to discuss the matter and someone (Olearius does not say who) recalls that Bruggeman’s orders had angered some of the villagers. But since nothing can be done to change the past, they decide that the only way forward is to take courage, and – having inaccessible mountains on one side, the sea on the other, and the barbarians before them – it would be more honorable to die nobly than fall alive into the hands of the Tatars.

“Our greatest misfortune,” Olearius writes, “was, that there were differences among ourselves. Ambassador Bruggeman carried on with his private designs, and found fault with whatever others advis’d, especially those among us who any way pretended to Learning. Certain it is, that, instead of contributing his endeavors to our preservation, he would have contriv’d our ruin, could he have done it without danger to himself.”

In the next episode, we find out how long the company must endure the Metropolis of all Dagestan, how many die at the hands of the Tatars, and how many are captured and sold into slavery, on the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post