Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 23: Isfahan, Ispahan, or Spaam?

They say that the City of Isfahan was once called Hecatonopolis, and that 2nd century Roman astronomer Ptolemy referred to it as Aspadana. In old Persian, the city was known as Sipahan, the plural form of a word meaning “the gathering place for armies,” and plural because the original city consisted of seven villages.

The site of the present day Isfahan was also known as Yahoudieh, a settlement for exiled Jews from the kingdom of Nebuchadnezzer of Babylon. Some credit that ancient Jewish colony to Queen Shushandukht, the Jewish wife of Yazdgerd I, who ruled Persia from 399 to 420 AD as part of the Sassanid dynasty. Arab Muslim tribes captured the city in 642 AD and named it Aljibal, meaning “mountains.”

Tamerlane conquered the city in 1387 AD and named it Ispahan – with a p – by switching the first two letters of the old Persian name. The Persians call it Isfahan – with an f – from an Arabian word meaning rank or battalion.

Muhammad ibn Arabshah (1389-1450), an Arab writer and traveler who lived under the reign of Timur the Lame and wrote The Life and Actions of Tamerlane among other works, called the city Isbahan with a b – as in “boy.”

Giosafat Barvaro, a merchant of the Republic of Venice, a Senator, and ambassador to Persia in 1472, called it Spaham. From 1436 to 1452, Barvaro lived in the city of Tanais, on the River Don near the Sea of Azov in what is now southern Russia. An ancient Greek city, it was destroyed by the Goths in 330 AD, refounded by the Venetians in the 14th century, taken by the Republic of Genoa in 1332, conquered by Tamerlane in 1392, by the Ottoman Turks in 1471, by the Russians in 1696, again by the Turks in 1711 and by the Russian Empire in 1771. Today, Tanais is an archaeological site. Nearby, Rostov-on-Don is the largest city in southern Russia and an important city in the current war against Ukraine.

The ambassador of Venice to Persia in 1473, Ambrogio Contarini, called the city Spaa, Spaam, and Aspacham. The House of Contarini is one of the oldest families of Italian nobility, and a founding family of Venice. In its heyday, the family produced eight Dukes of Venice, 44 Procurators of St. Mark – a position second in power only to the Duke – and numerous other ambassadors, diplomats, soldiers, admirals, and bishops. A branch of the family still survives in Sicily, but the Republic of Venice – which lasted for 1,100 years – ceased to exist when Napoleon invaded in 1797.

For our story, of course, the year is still 1637, and according to our intrepid author, Adam Olearius, Isfahan’s real name is Ispahan with a p. We will continue to call it Isfahan with an f.

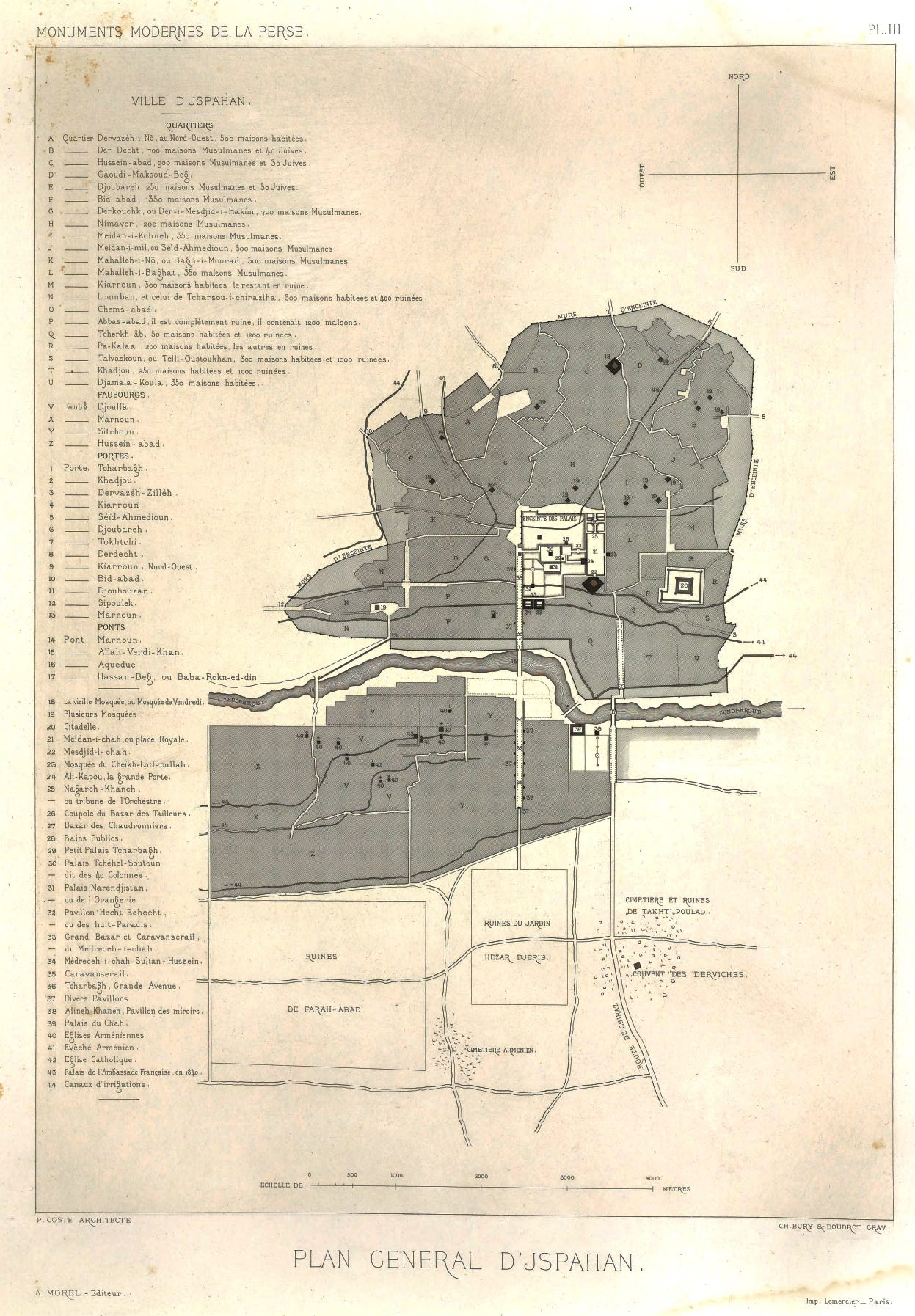

The city lies in the province of Erak, which is ancient Parthia, on a spacious plain with mountains on all sides, making the city look like a geographic amphitheater. Counting all of its suburbs, the city is more than eight German Leagues in circumference, or some 36 miles, which is about as far as a man can travel in one day.

There are 12 city gates, of which only nine are open, more than 18,000 houses, and about 500,000 inhabitants, which works out to nearly 25 persons per house.

The city’s earthen walls are low and weak. The ditch surrounding it adds nothing to its defense, and in both summer and winter a man may pass over the ditch without getting his feet wet.

The Zayandeh River comes out of the nearby mountains and divides into two branches before entering the city. The river supplies the whole city with water, Olearius writes. There is hardly a house which does not have water pipes, and those that do not are close to public wells. At its widest point, the river is just as wide as the River Thames in London.

Shah Abbas had attempted to merge the Zayandeh and Abkuren rivers with a construction project that employed thousands of Persian laborers. After 14 years, only several hundred feet of the unfinished canal remained. And then Abbas died, leaving the completion of the project to his grandson Safi, who does nothing to finish the job.

“If Ali, the Patron and great Saint of the Persians, had lived in that time,” Olearius writes, “he might have done Shah Abbas a very great kindness, by opening that Rock at one blow with his Sword to make way for the River, as he did with the River Aras, through the Mountain, which he opened with his Sword, and which, to this day, is called the Straits of Ali.”

Olearius tells us that Isfahan was twice destroyed by Tamerlane, but does not provide dates, and I can find only one siege by the man who once was the world’s most successful military commander. In 1387, the city surrendered to avoid the utter destruction suffered by others during the conquest of Persia. Soldiers arrived to collect the tribute, and the process was almost complete when a deadly accident happened.

One night a young blacksmith was playing a small drum for his own amusement. Some of the citizens thought it was an alarm, so they gathered their forces and attacked the occupying soldiers, killing some three thousand and shutting the gates against the army camped outside. Tamerlane stormed the city and, rather than simply allowing his soldiers to pillage and slaughter, he ordered every soldier to bring him a certain number of heads. As one version of the story goes, some soldiers purchased their allotment of heads rather than execute people who did not resist. Exactly how many died is unknown, but estimates range from 70,000 to 100,000, and eyewitness accounts say at least 30 pyramids of 1,500 heads each were built throughout the city.

“I trusted the people of Isfahan and delivered the castle into their hands,” Timur wrote in his book titled Institutes Political and Military. “And they rebelled, and the governor whom I had placed over them they slew with three thousand of the soldiers. And I also commanded that a general slaughter should be made of the people of Isfahan.”

We heard about Tamerlane’s conquests in episodes 6 and 10. Born in 1336 in Uzbekistan, he died in 1405. In addition to being a soldier, he was also an accomplished scholar who spoke multiple languages. The most reliable estimate of his total death count is 17 million, which at the time was about 5% of the world’s population.

Olearius also relays a story told by Giosafat Barvaro, in which Isfahan was destroyed “about twenty years before” 1471 AD by a king named Chotza who desired to “punish this city for its rebellion.” I have been unable to identify which king this refers to, but like Tamerlane, he commanded his soldiers to bring him heads belonging to the inhabitants. Apparently, there were not enough men in the city, so the soldiers cut off women’s heads, shaved them, and brought them to the king. Thus, “the city was so depopulated that there were not people enough left to fill the one-sixth of it.” In other words, according to this story, about 85% of the city was vacant after the murdering was done.

The city began to recover under Shah Ismail II, Olearius tells us, and after Abbas transferred his court from Caswin to the growing city, travelers reportedly called Isfahan “Half the World.” This, said 17th century Persian historian Iskandar Munshi, who wrote The History of Shah Abbas the Great, was because “they only describe half of Isfahan.”

What contributes most to the greatness of this city are the markets, the bazaar, the public baths, and the palaces, Olearius writes. But even better are the city’s gardens, and many houses have two or three gardens and most have at least one.

Gardens are where they “make greatest ostentation of their wealth,” but unlike Europeans, the Persians prefer fruit trees over flowers. The best thing about the gardens are the fountains, which are very large, with more than one basin, and water from them is used to irrigate the gardens.

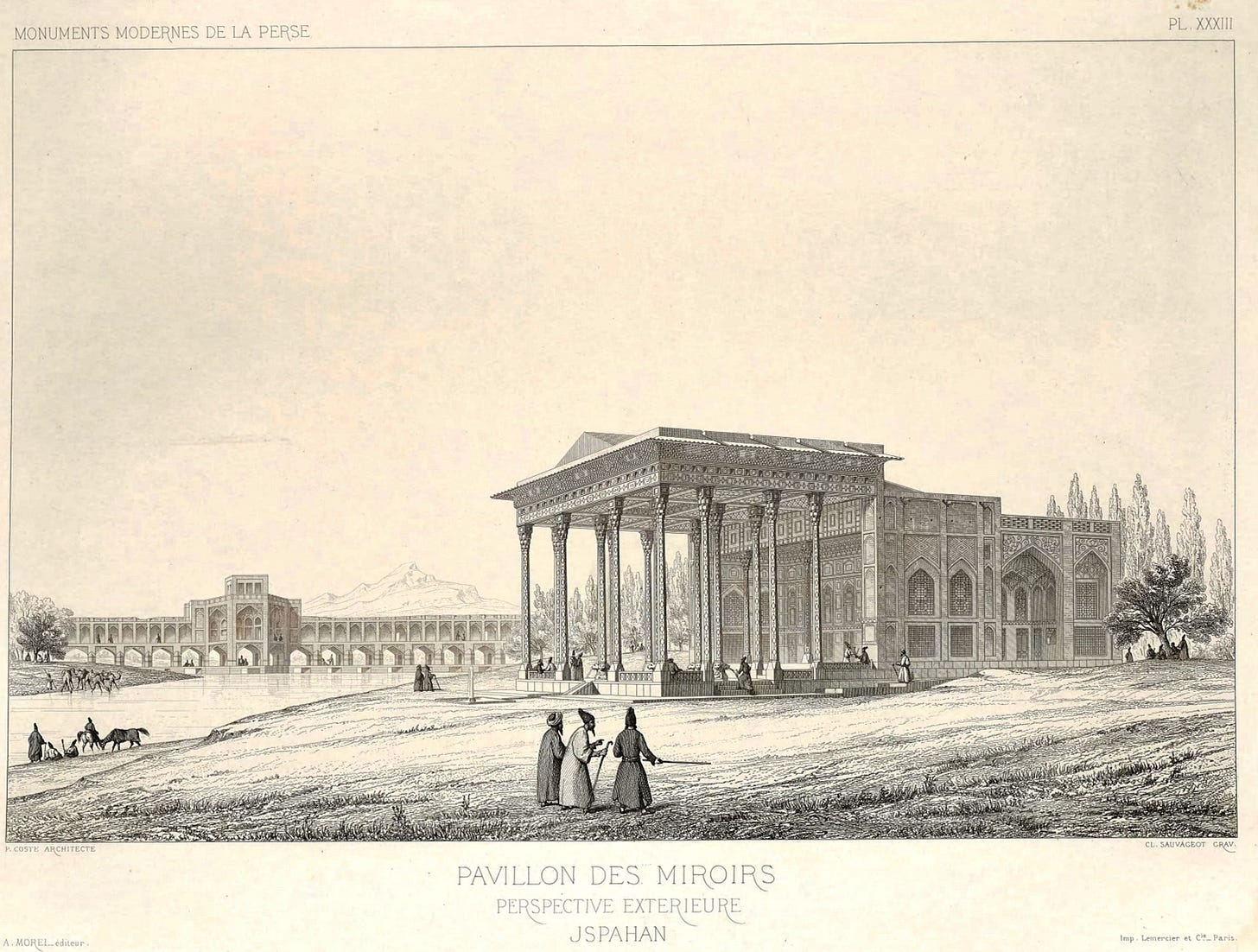

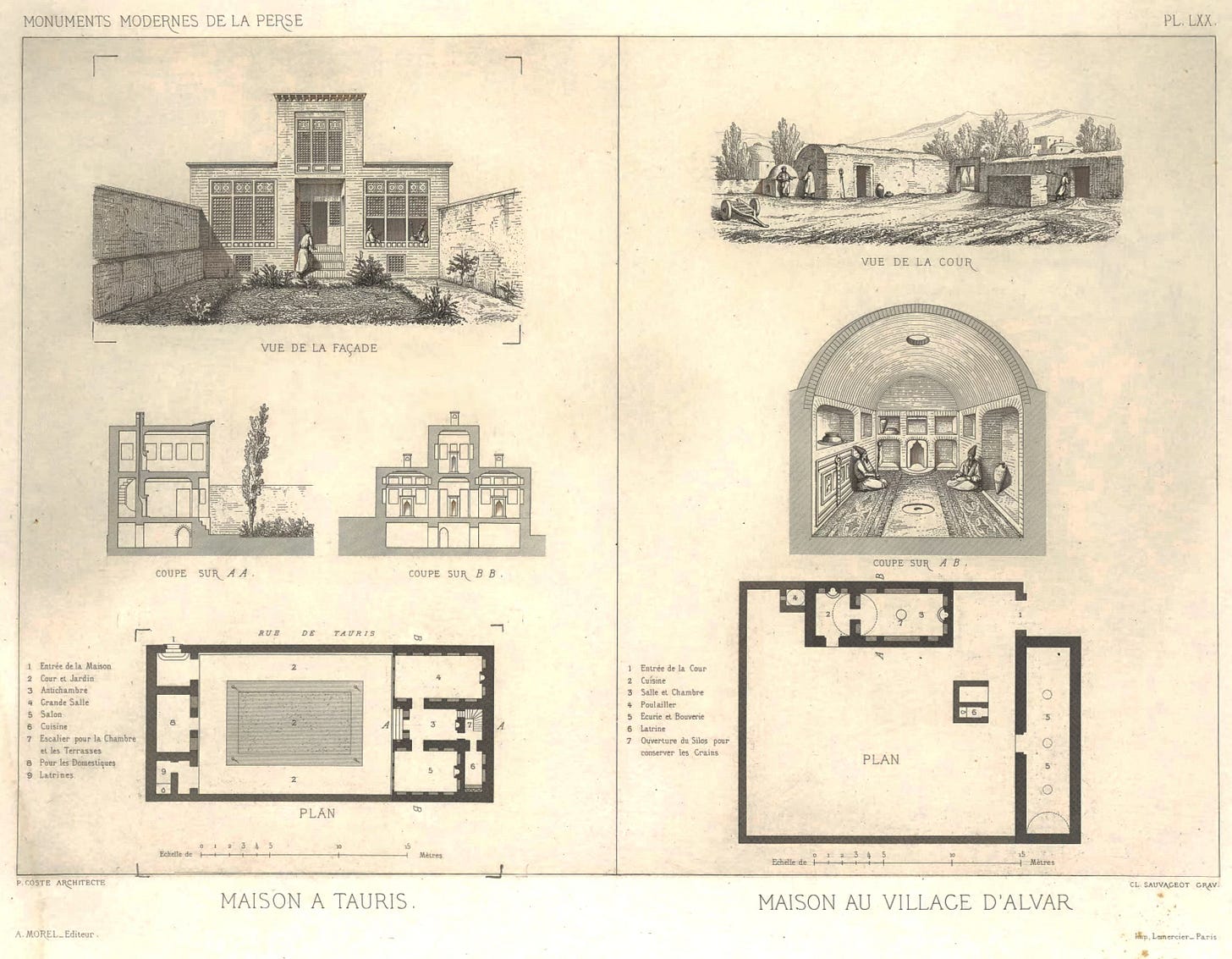

Most persons of quality build summer houses in their gardens, which are enclosed with a row of pillars and have a room at each corner where guests can enjoy the breeze regardless of its direction. Many of these houses are more beautiful than the homes they live in, for although it is true that their homes and palaces are magnificent on the inside, most the city’s homes are ugly on the outside, being built of earth or brick.

Their homes are generally square and have four stories. The windows are often as big as the doors, and because the buildings are not very high, the window frames ordinarily reach up to the roof. They don’t have glass panes, but in the winter lattice-work frames covered with oiled paper are mounted to keep out the cold.

There is so little wood in most of Persia that open fires are uncommon. Instead, each home has a stove on the ground floor which consists of a hole filled with burning coals and covered with a plank or a low table. Over that is a large carpet. To prevent harmful fumes from filling the room, Olearius tells us that “certain passages and conduits under ground” draw the smoke away. In the winter months, people warm themselves around the stove by sitting on the ground, with their feet under the table and blankets up to their chests to keep in the heat.

Before Abbas made Isfahan the capital in 1598, the streets were so wide that 20 horses could walk abreast. But now the streets are so narrow that if a man meets a mule-driver guiding 20 mules through the street, he must step into some shop and stay there till they pass by.

All the streets next to the main marketplace are very narrow, but the maidan itself, constructed by Abbas beginning in 1602, is so large – at 1,673 feet long by 518 feet wide – that Olearius “cannot imagine there is any in Europe comes near it.” It is called the “Design of the World,” and unites all of the facets of the Safavid society into one spatial diagram: worship, commemoration, sovereign administration, and trade. All the 200 commercial buildings that face the square are two stories high, all are built of brick, and all have a vaulted shopping space on the ground floor. On the side towards the shah’s palace are goldsmiths, jewelers, a hospital, the state mint, a public bath, and a caravanserai. Opposite to them are silk, wool, and cotton merchants, and the drinking taverns. Just outside the square are many other buildings, including schools, factories, mansions belong to merchants, and artisans’ dwellings.

Trees are planted all around the marketplace, and their branches are cut so the buildings are not obscured, which makes for a very delightful prospect. Water flows in a raised stone channel at the foot of the trees, drains into basins at two of the corners, and is then carried underground to other places in the city.

The merchants work only in their shops, leaving slaves and apprentices to do any other labor that might be required for the business. Every trade has its own quarter or street assigned to it, where no other commodity can be sold, and Olearius says he finds a certain delight in this kind of order. Music plays over the square every night at sunset or when the shah comes and goes from his palace. “They have this kind of music in all the cities of Persia,” Olearius tells us, “and they say Tamerlane first introduced that custom, which hath been observed ever since.”

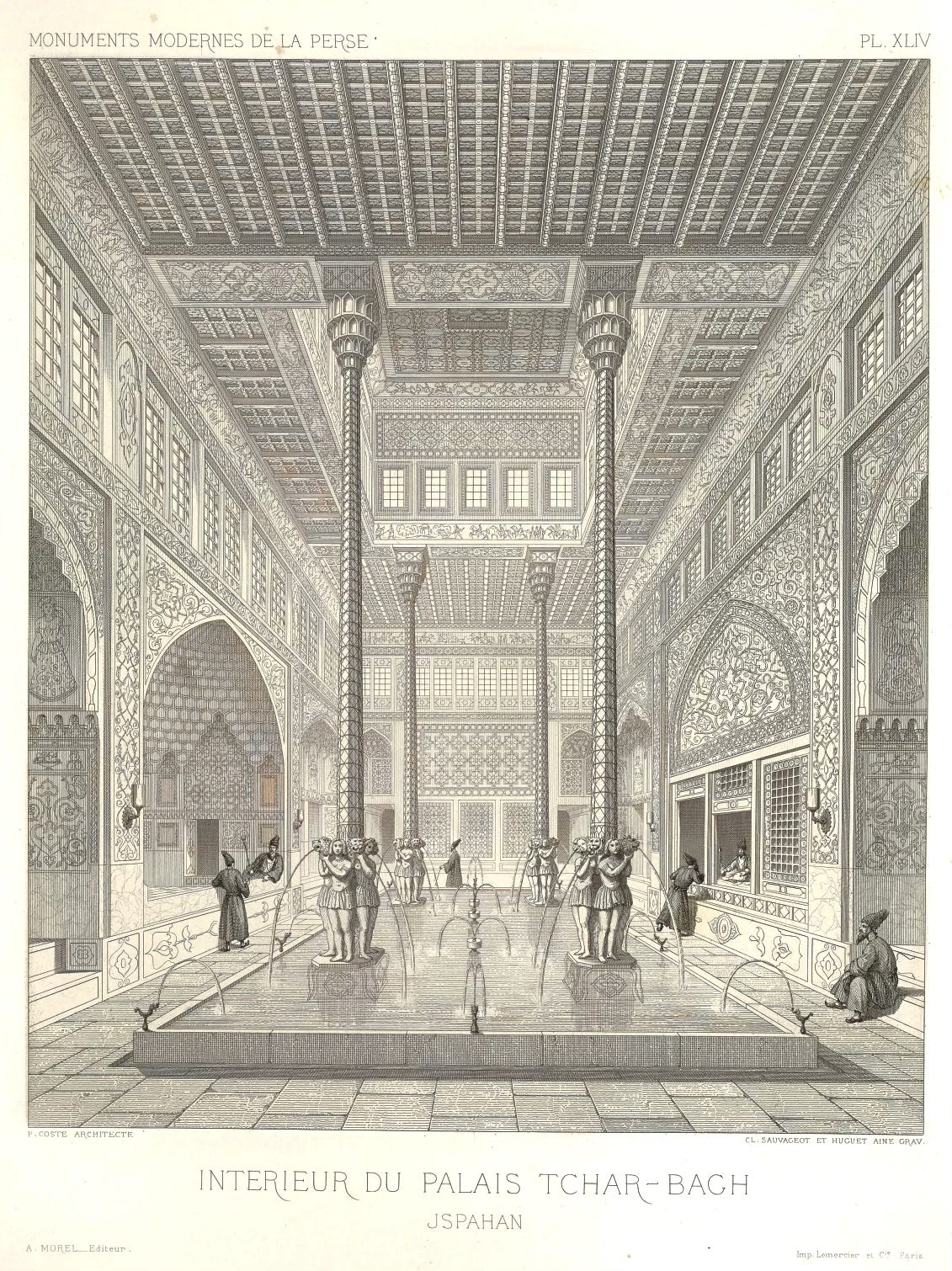

The five-story imperial palace occupies the entire west end of the marketplace. At the main gate, also called the Sublime Gate, are several cannons with no carriages, and because of this they cannot be fired. The palace itself has no fortifications and is surrounded only by a high wall. There are three or four guards on duty during the day, but 15 at night and another 30 inside. Each day, the captain of the guard delivers a list to the shah containing the names of all the guards, so that he may know whom he may confide in, and by what persons he is served.

The place was built by Abbas on the grounds of the old Naqsh-i Jahan gardens, which have been there since the 10th century. Inside the walls are all the chambers, apartments, dining rooms, meeting rooms, music rooms, dancing halls, and courts of justice for the shah himself, and all of the shah’s administrators, eunuchs, wives, and concubines. The buildings are clustered according to their function, and each set of buildings is nestled inside its own individual garden. As noted in episode 22, Abbas had 500 concubines, which gives us some indication of the scale of the place, but in 1637 the lush palace complex measures three miles in circumference.

A fortified castle containing the shah’s treasury, weapons and ammunition is located behind the palace grounds, and is occupied by a strong garrison of soldiers.

Near the entrance to the palace, about 40 paces to the right side of the outer gate, another entrance called God’s Gate opens into a spacious garden with a chapel. This is the sanctuary where – as we heard in episode 22 – Mr. Lion Bernoldi fled to avoid imprisonment by Ambassador Bruggeman. Anyone who fears prosecution in civil or criminal matters – even murderers and assassins – can find refuge here until the matter is settled. It must be noted, however, that Persians considered thievery to be the worst crime of all, and thieves could obtain sanctuary only for a few days before being expelled from God’s Gate.

A rich and magnificent mosque dedicated to the Mahdi – the Twelfth or Hidden Imam – stands to the south of the marketplace. Begun by Shah Abbas, its construction is still ongoing in 1637, and Olearius says Shah Safi is facing the walls with marble.

Twelver Shi’ism believes in twelve infallible Imams, Ali and his descendants. Although the last Imam disappeared as an infant in 873 AD, he is still alive and will return as the messianic Mahdi shortly before the second coming of Jesus Christ. This return will herald the end of evil and injustice in the world. As Olearius describes it, “The Persians would have it believed that the Mahdi is not dead, but lies hidden until the Day of Judgment, when he will mount Ali’s horse, ride all over the world, and convert people to the religion of Muhammad.”

Shi’ism became the national religion of Persia in 1502 AD under the first Safavid shah, as a means of defending against the threat of the Ottoman Empire, which had defeated the Byzantine Empire in 1453 and established its capital at Constantinople.

The Ottoman Turks had declared themselves the defenders of Sunni Islam, and felt threatened by the militant Shia state of Persia. As noted by Father Sanson, a French missionary who lived in Persia in the second half of the 17th century, there was no spirit of nationality or patriotism as we know it today. Religion was everything. “The pains that Sheikh Sefi took to establish a particular sect, which is so different from and so contrary to that of other Moslems,” Sanson wrote, “is a very good means of preventing the people from revolting at the solicitation of the Ottoman.”

In the middle of the Isfahan marketplace stands a high pole. On sporting days, a melon, or an apple, or sometimes a rough wooden plate filled with money, is placed on top of the pole, and mounted archers riding at full gallop attempt to hit the target with an arrow. It is common to see large bets placed on the outcome of the game, and the winner is obliged to buy dinner for all the participants. The sport is called pole archery, and it is also common in Europe, but in those countries the target is a wooden bird which Olearius calls a parrot. He doesn’t tell us how tall the pole is, but modern versions of the game use poles 110 feet high.

Olearius tells us Persia has the best horses in the world, and that the people of Isfahan also throw javelins, play polo, and conduct horse races in the marketplace. When the shah comes to watch, he sits in a little wooden lodge on four wheels which can easily be moved from one place to another.

The taverns and other drinking houses are on the other side of the square, and are of the usual types. Some have clients who value their reputations. Those which do not Olearius calls the “infamous and common receptacles of a sort of people who divert themselves there with music and dancing of some of their common drabbs.” Our translator Davies uses the word drabbs here – D-R-A-B-B-S – which is probably from the low German drabbeln circa 1400 AD, meaning “to make dirty, as by dragging; to soil (something), trail in the mud or on the ground.” These drabbs apparently “excite the brutalities of the spectators” with obscene gestures, and sometimes “draw them along into some public places where they permit the commission of these abominations as freely as they do that of ordinary sins.”

The tea houses, on the other hand, attract “only persons of good repute” who spend their time at chess or a game similar to what Davies calls tick tack, which in 16th century Europe was a form of backgammon, possibly similar to the French game trictrac.

The Persians are better chess players than the Russians, Olearius writes, “whom I dare affirm to be the best gamesters at chess of any in Europe,” and he tells us two stories about the game which, he is quick to say, are not true.

First, there was a great book on the game of chess recently published in Germany, in which the author wrote that the ancient Goths and Swedes could tell who would be a good son-in-law by how well he played chess.

And second, there was a King of Babylon who was so tyrannical that none of his advisors dared to tell him how dangerous his policies were to both him and his country. So one of the Lords of his Council invented the game of chess as a means of instructing the king on how to make wise decisions. The game, which pitted two great kings against each other – each with their queens, their officers, and their soldiers – wrought a greater impression than any explanation could possibly have done.

“Of all the shops I saw at Isfahan, I was not pleased so much with any as that of a Druggist, who lived in the Maidan, on the left hand as you go to the mosque, by reason of the abundance of the rarest Herbs, Seeds, Roots and Minerals it was furnished with,” Olearius writes.

There is hardly any country on earth that does not send its merchants to Isfahan, but there are perhaps more Indians – more than 12,000 by his reckoning – in the city than any other nationality. “Their stuffs,” he writes, “are incomparably fairer, and their commodities of greater value than those of Persia; inasmuch as besides the musk and ambergris, they bring great quantities of pearls and diamonds.”

Ambergris is a waxy substance produced in the digestive system of some sperm whales. When it is fresh, it smells like – well, exactly like what you would expect: whale feces. But it develops a sweet, earthy scent as it ages, and has been valued by the perfume industry for hundreds of years because of its ability to improve other smells.

The Compleat History of Druggs, first published in Paris in 1694 and translated into English in 1712, says ambergris is “the dearest and most valuable commodity we have in France, and a thing the least understood, its nature and origin being most contested.” It comes mostly from Lisbon, the author says, and is made of “honeycombs the bees make upon the large rocks,” which, when heated by the sun, loosen and fall into the sea.

The author notes that Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, whom we have met on several occasions, once found a 42-pound piece of ambergris on the Isle of St. Maurice near Madagascar. Aside from its use in perfume, it is also an antidote to poison, and a good medicine to warm the stomach, prevent gout, and strengthen the debilitated parts. In men, it makes the spirits gay and provokes lust, but women should avoid it because raises the vapors.

And who is the author of that history of drugs? One Monsieur Pierre Pomet, chief druggist to King Louis XIV of France.

Next time we visit the suburbs of Isfahan, explore the monasteries of Italian and Spanish monks, hear how the shah prevents inflation, and why, according to the Persians, dogs and cats hate each other, on the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post