Welcome to The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors, the epic story of a 17th century trade expedition from Germany to Persia that failed so completely its leader was publicly executed upon his return. This is Episode 18: Across the Persian Desert.

The Holstein trade mission leaves Caswin on the evening of July 13, 1637, the baggage and sick people leaving first and the gentlemen following later that night.

This is the final leg of their outbound journey from the German port city of Hamburg to the Persian capital of Isfahan that began almost four years ago. Along the route they’re taking, Persia is about 500 miles wide from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf, and although the 300-mile road to Isfahan does not cross the harshest deserts in the country, the conditions described by Adam Olearius are still very harsh indeed.

The interior deserts of Persia are not vast expanses of sand dunes, but instead vast expanses of sand and stone, half of which is covered with saline mud. The country’s few rivers generally flow out of the peripheral mountains toward the center of the desert plateau, where the water not lost by evaporation sinks into the sand.

We discussed the Persian irrigation systems in the last episode, and French traveler John Chardin – whom we first mentioned in episode 14 – wrote that although water is the “cause of all fruitfulness in Persia … the want of people does not proceed from the barrenness of the soil, but the barrenness of the soil from the want of people.”

Our ambassadors are crossing the western edge of this desert in Caswin province toward the city of Kom and a great dry salt lake. Today, the province is a regional communications hub, with intersecting freeways and railroads, industries like cloth weaving, cotton ginning, wool carding, flour milling, food processing, and electrical equipment manufacturing. It is more desolate in 1637, and the Germans make 15 miles the first night through a great plain, coming to a small village where, at a distance, the houses look like ovens.

Ambassador Crusius falls ill. Not able to ride on horseback, he is carried on a litter for several days. Albrecht von Mandelslo is, so far, the only person who hasn’t been sick, and Olearius writes that his friend closely observes the symptoms of others and makes notes that could fill an entire book.

As noted in episode 2, Olearius eventually does publish Mandelslo’s account of the trip – which includes a journey into India and a sea voyage home – but I have not yet decided whether to include that book in this podcast.

They reach the village of Araseng on the morning of July 15. A garden near a river grows pomegranates and almonds, which the travelers find greatly refreshing. From here the road gently rises into a mountain pass with an elevation of some 5500 feet, and they make another six leagues – roughly 27 miles – to a caravanserai named Choskeru. Carved on the walls of the building are the “names and devises” of people from many nations who, like people from every era in history, wanted to leave some evidence that they had been there.

Until now, they have been following what is today Highway 49, which intersects with Highway 65 – the road to Tehran – and falls a thousand feet into the city of Saba. They arrive before sunrise on July 17. Their guides halt the caravan some distance from the city, to give them time to send a welcome party. The city is not very big, but like others they have passed through its towers make it look more substantial than it is. Its earthen walls and homes are mostly destroyed, but it does have very fair gardens that grow excellent fruits. Cotton and rice are also grown in great quantities.

They leave on the evening of the same day, but I’m not sure exactly what route they take. The caravanserai that Olearius calls Schach Ferabath does not exist on a modern map, but they are headed toward the city of Kom that lies to the southeast of Saba.

The heat at the caravanserai is so bad they strip down to their underwear. They pitch tents to acquire some shade, but wind out of the mountains comes in blasts that are hotter than the heat of an oven. They escape into the caravanserai and Olearius tells us they cannot walk five or six steps without burning their feet.

They reach Kom on July 19. The governor meets them with 50 gentlemen on horseback and a troop of gymnasts on stilts. I had to read this section a few times to make sure I was getting it right, but it does appear that men on stilts – Olearius calls them “tumblers” – provide entertainment for the ambassadors all the way to their quarters in the city.

Musicians are playing in the marketplace, and the streets have been watered to keep the dust down. Olearius tells us that the latitude and longitude of Kom claimed by the Persians is incorrect, and so he corrects it for his readers.

The fact that this ancient city was once much bigger can be seen by the ruins of its old walls, which lie much further out from where they are now. Located in a plain some 50 miles from a salt lake, it is 125 miles from Caswin, 75 miles from Tehran, and about 160 miles from Isfahan. Freshwater springs on the mountain of Elwend send a small river down to the entrance of the City, and Olearius says that about three years before their visit the river had flooded and carried away more than 1,000 houses. In the city’s gardens grow all sorts of excellent fruits, and cucumbers that are more than two feet long. The Persians pickle these with vinegar, but no salt, so that the taste is unpleasant to people not accustomed to it.

The ground is good for farming and produces all sorts of grain and cotton, but the principal trade goods produced by the city are pottery and sword blades. The blades are the best in the country, and made of steel from Niris, about 280 miles southeast of Isfahan, which is still a modern steel town today. The pottery is also very much esteemed, especially the great pitchers that will keep water fresh and sweet even in the greatest heats of summer.

French traveler John Chardin tells us that Persian mines produce sulfur and salt peter, along with the raw materials for making products of iron, steel, brass and lead. The steel forged in Persia contains so much sulfur, he says, that “if you throw the filings on the fire, they will go off and make a report like gun powder.” Their craftsmen don’t understand very well how to temper it, he says, and they have no method of making wheels, springs, or other delicate pieces. “But the steel does take a very good temper, which they do by wrapping it up in a wet cloth instead of putting it into a trough of water.” Mixed with Indian steel, they call it “washed steel,” which known among the Europeans as Damascus Steel.

Olearius tells us the inhabitants of Kom are “somewhat light-fingered” and apt to steal anything that is not locked up. “We had hardly alighted, but our pistols were taken away, and what was not locked up immediately vanished,” he writes.

Several of the Germans are plagued by the “bloody flux,” which he says is caused by eating too much fruit and drinking too much water. Today, we know the disease as dysentery, an inflammation of the intestines from a bacterial infection that causes bloody diarrhea. In extreme cases, people can pass more than a liter of fluid per hour, causing rapid weight loss, and it appears that the Germans have a pretty bad case of it.

They leave Kom on July 21, going south along what is now the Persian Gulf Freeway, and on the 23rd they reach the village of Sensen. A man identified only as Gregory, a Muscovite who served as a Persian interpreter, dies here. Two more Russian servants die of the bloody flux along the road as they leave town. They take the bodies with them to be buried at their next stop, the city of Kaschan.

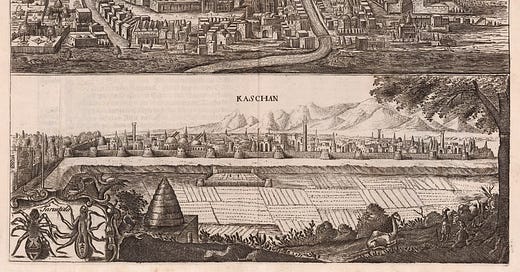

The city is a vacation spot for the Safavid kings. They pass by an equestrian center used for “tilting and running at the ring,” an ancient sport in which a horseman rides at full gallop and tries to insert his lance through a small metal ring. The shah has a garden and summer home here, and the Germans are told that the house has a thousand doors and windows.

In 1637, Kaschan is also one of the most populous and most eminent trading centers of any in Persia, and the best built city the Germans have seen yet. Olearius tells us the houses, palaces, caravanserais, bazaars markets, store houses, and galleries are the noblest he sees in all his Persian travels.

The city is constantly full of a great number of foreign merchants, most of them from India. Its farmers produce wheat, wine, and fruits in such abundance that Olearius readily acknowledges what the preacher John Cartwright wrote in his travel book in 1611: that the poorest and most indigent residents have not only what is required for their subsistence, but also some luxuries. What the city needs most, however, is fresh water. Wells must be dug very deep, and the water they recover is so distasteful and corrupt it is almost undrinkable.

But he also says that Cartwright’s description of the “Institution of Youth” is not accurate. “I must confess,” he says, “that I could not observe the excellent order and commendable policy” that Cartwright says he observed about the city’s family structure. On the contrary, Olearius finds that most parents are lazy, walking in the market or talking in the shops while leaving most of their work to be done by slaves. In addition to having many slaves, parents bring forth great numbers of children through polygamous marriages.

John Cartwright’s 1611 book, published in London, was titled Wherein is set downe a true Journall to the confines of the East Indies, through the great countreyes of Syria, Mesopotamia, Armenia, Media, Hircania and Parthia, With the Authors returne by the way of Persia, Susiana, Assiria, Chaldaea, and Arabia. There is some debate about whether John Cartwright was ever a preacher. Even though he was listed as being employed as a preacher by the Levant Company, his book makes no mention of preaching, neither in any of the places he went nor to any congregations.

He did travel through many of the same cities as our Germans, and Olearius tells us he was right about the scorpions.

“For of these, there are, about Kaschan, more than at any other place of Persia, and such as are so dangerous, that they have occasioned that Malediction: may the Scorpion of Kaschan pinch thee by the hand. We found some of them in our Lodging, as black as coal, about the length and compass of a man’s finger, and we were told that these were the most dangerous of any sort of them.”

Because of the scorpions, the locals never sleep on mattresses laid on the ground, as they do in other cities, using a bed frame instead. Olearius is the only member of the trade mission to get stung by one.

“It was my misfortune to be the only man of all our retinue that had occasion to make trial how venomous this Creature is,” he writes. “For lying down upon my Bed at Scamachie, in our return from Isfahan, a Scorpion stung me in the throat, where it made immediately a swelling about the length of my finger. As good fortune would have it, our Physician immediately applied the Oil of Scorpion, gave me some Treacle, and put me into a sweat: which delivered me from the greatest of my pains at the end of three hours, but I had still some pain for the two days following, and it was as if I had been pricked with a Needle: nay indeed for many years afterwards I have been troubled with the same pains at certain times, especially in Autumn, much about the Sun’s entrance into Scorpio.”

The Persians have a different remedy for scorpion bites: they apply a piece of copper money to the wound, leave it there for 24 hours, and then replace it with a plaster made of honey and vinegar.

Olearius also tells us about a spider he calls a “tarantola,” that does not bite or sting but deposits its venom like a drop of water that causes immediate and insufferable pain in the stomach and head. The infected person falls into a profound sleep that can only be cured by crushing one of the spiders onto the original wound, by which all the venom is drawn out of the body.

If the spider cannot be found, another remedy may be used. The sick person is laid on his back and fed as much milk as possible. Then his body is laid on a wooden frame. Cords are attached to the four corners of the frame. The frame is hung from the ceiling, then wound up and suddenly released so that the violent twisting motion makes the patient vomit all the milk. A greenish crud-like substance emerges with great violence and extreme pain. But this is only a partial cure. The patient lives, but continues to experience severe pain, especially during the same season of the year he was originally infected.

The good news is that the spider only lives in the country, and that sheep feed on it. The bad news is that the creature can sometimes be found in straw used to thatch the roofs of homes in the city.

The heat is so excessive in Kaschan that they stay for several days to allow their sick to recover. They leave on July 26 as soon as the moon is up and travel six leagues to a caravanserai called Chotza Kassim. The rooms are so small and nasty that they pitch tents in a nearby garden, in the shade of cypress and pomegranate trees and on the bank of a small river. The gentle noise of running water comforts everyone.

They reach the little city of Natens at four in the morning on July 28, after traveling through desert and barren grounds. The local caravanserai is comfortable, has several springs of fresh water, and is well stocked with fruit. A still-healthy Albrecht Mandelslo climbs one of the nearby mountains and finds a tower built by Shah Abbas in memory of the time one of his falcons killed an eagle on that very spot.

Natens is about 60 miles from Isfahan. The Germans could have traveled that distance in two days, but it takes another five days to get there. They cross a 7,000-foot mountain pass on July 29 and stay in a caravanserai called Dombi, a name that appears on modern maps today. Some representatives of the Persian Chancellor come to meet them, but Olearius does not tell us why.

They spend two days in a village called Kuk that I cannot find on the map, and leave two hours before sunrise on August 2. But they make less than 10 miles that day, stopping at one of the shah’s houses, where they spend the last night before entering Isfahan, which they do on the morning of August 3, 1637.

Olearius calls it the Metropolis of the Kingdom. They are met by one of the principal officers of the court, one Isachan-Beg, 200 horsemen, and two great Armenian lords, who conduct them to their lodgings. The dust kicked by up by this procession is so thick that they reach the gates of the city before they can actually see where they are. As in other cities, the streets and rooftops are overflowing with curious onlookers.

They pass a large market and the shah’s palace, and cross the Zayandeh River into the Armenian quarter of the city. We will hear more about this important section of the city in the next episode, but for now the Germans begin to unpack their things and settle into homes of the most important Armenian merchants. A banquet is served, and the first course arrives on 31 silver dishes filled with all sorts of fruits, including melons, citrons, quinces, pears, and some not known in Europe. That is followed by 50 dishes of rice of all colors, mutton, fowl, fish, eggs, and pies.

After dinner, the local representative of the Dutch East India Company, one Nicholas Jacobs Overschle, comes for a visit and informs the ambassadors that he has received orders to oppose Holstein’s negotiations with the shah. But he also says he will do everything he can for the ambassadors personally, and the ambassadors respond by sending him away with as much liquor as his servants can carry.

After leaving Hamburg three-and-a-half years ago, everyone feels immense joy that they have finally arrived in Isfahan. Olearius tells us the ambassadors are eager to begin negotiating the silk trade agreement that will finally elevate Holstein and Duke Frederick onto the world stage where they belong.

The joy evaporates four days later.

In the next episode, two servants insult each other on the street, the insults escalate into assault, the assault escalates into a beheading, the beheading escalates into a street war, and we find out how many Germans and Indians are killed, and what the shah wants to do about it, on the Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors.

Share this post